Why America Must Invest in Intel Foundry

The U.S. needs a private Intel Foundry flush with patient capital

By Austin Lyons and Mark Rosenblatt

An American-owned, leading-edge semiconductor foundry is a strategic imperative for national security, particularly given emerging AI-driven warfare capabilities. See Futurence for more context.

Intel’s Foundry remains America’s strongest prospect for semiconductor independence, but its long-term viability is under growing risk.

The following report outlines the rationale for government intervention to ensure Intel Foundry's success and safeguard U.S. interests.

Securing Intel Foundry

Intel is composed of two main divisions:

Intel Products Group – A fabless unit designing Intel’s core products.

Intel Foundry Services (IFS) – A semiconductor manufacturing division that serves both Intel Product Group and external clients

For a quick refresher, see Understanding Intel.

Intel Foundry Services (IFS) is broadening its focus from supporting Intel products to serving external clients. Initially offering lower-value advanced packaging services, IFS is now advancing to high-value chip fabrication for major players like AWS and Microsoft123. These chips will be manufactured using Intel's 18A process node, the pinnacle of its ambitious “Five Nodes in Four Years” (5N4Y) strategy to reclaim the leading edge in semiconductor manufacturing4. Achieving this vision requires a multi-year investment plan exceeding $100 billion in leading-edge manufacturing, advanced packaging, and R&D facilities, spanning U.S. locations such as Arizona, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oregon5.

Although Intel Foundry is being established as an independent subsidiary inside Intel, it is nowhere close to profitability; the quarter that ended October 31 saw an operating loss of $5.8B.

Despite being several years into its investment plan, IFS is not on the cusp of breaking even. While the first 18A chips are expected in 2025, high-volume manufacturing won't happen until 2026, and even that doesn't guarantee profitability. Reaching profitability requires significant production volume, as it takes a nearly-filled fab to reach profitability. As we’ll explore later, Intel faces significant challenges in achieving the fab utilization needed for profitability.

Intel is currently funding Foundry’s substantial capital and operating expenses through revenue from its Product Group and fab co-investment from Brookfield and Apollo. However, the Product Group faces consistently falling revenues and narrowing profits. These challenges stem from missing massive markets—mobile and AI—coupled with a faltering cash-cow CPU business.

More challenges lie ahead. A quarter of Intel’s revenue came from China in 2023; this will surely decline in the coming years6. Additionally, Intel Product Group outsources some manufacturing to TSMC while IFS works to catch up, which is a drag on profit margins.

As a result, Intel’s ability to fund IFS is a pressing concern. Intel Corporation reported negative free cash flow for the first nine months of 2024, carries $46 billion in debt, and continues to see a decline in stockholders’ equity. At the time of publishing, Intel’s stock was down more than 50% year-to-date.

Intel is working hard to find money and cut costs. Through the Chips Act, it was awarded nearly $8 billion in November and $3 billion in DoD funds in September. Intel also anticipates claiming the U.S. Treasury Department’s Investment Tax Credit, which may offset 25% of qualifying investments over $100 billion78.

Yet this support represents only a fraction of the capital Intel must secure to make IFS self-sufficient. And, as is typical with government funding, the disbursements will occur over time.

But Intel needs a lifeline now, tomorrow, and the day after. Its current financial position leaves no room for error. A further decline in product revenue or a hiccup that delays 18A’s timeline could have existential implications for the company and, by extension, national security.

Take a deep breath: investing $100B in capital expenditures is the easy part for Intel Foundry.

A successful foundry must first develop the transistor and packaging technologies necessary to support future process nodes—a challenging task, but one in which Intel has made progress, such as with advancements in backside power delivery9.

However, Intel's next step is much harder: economically achieving high-volume manufacturing. Even if IFS can make leading-edge chips with excellent yields at scale, Intel must still win enough customers from TSMC to fill its fabs.

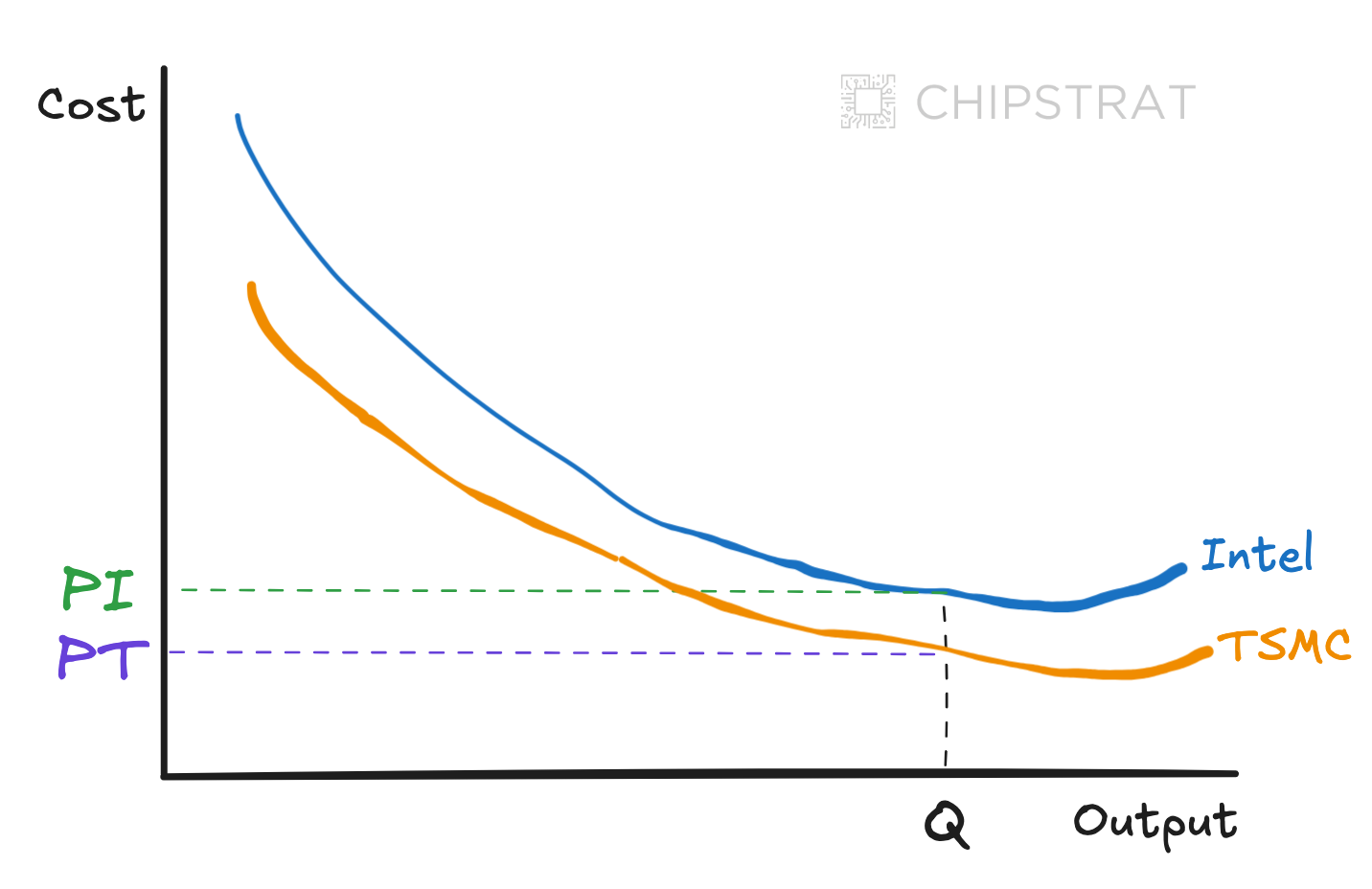

This is dire for Intel, as IFS is not cost-competitive with TSMC.

This begets a chicken-and-egg problem: IFS needs competitive pricing to win customers and unlock significant volume. However, to get competitive pricing, IFS needs significant volume.

Intel needs to “move down the cost curve” to price competitively:

Intel could try to scale volume by pitching itself as a second-source fab for customers whose products sell millions of chips yearly, like Apple iPhones, Nvidia AI servers, or Broadcom custom ASICs. However, this is a tough sell, requiring those companies to spend hundreds of millions of dollars in non-recurring engineering (NRE) costs to redesign their chips for Intel's manufacturing process10.

Adding to Intel’s challenges, these companies already rely on TSMC, which enjoys inherently lower costs due to factors like Taiwanese labor, greater production efficiency from years of experience, and, most importantly, a very large revenue base over which to amortize R&D.

But remember, IFS is not at scale, not yet at technology parity, and does not have a track record of operating a foundry business.

The harsh reality for Intel: 18A will launch with low volume and high prices, while TSMC's 2nm will have the opposite—high volume and low prices.

Companies are not motivated to use Intel if the per-unit costs are significantly higher. To unlock the volume needed to move down the cost curve, Intel must forward price, which means they need to price their chips at the competitive price demanded by the market.

This means starting with negative margins that gradually improve until reaching break-even and eventually profitability.

Note that the forward price doesn’t necessarily need to be equal to TSMC if there are other benefits to Intel’s chips. For example, a particular customer may be 10th in line at TSMC, whereas they could be at the front of the line with Intel and receive their chips in full allocation 6 months sooner.

But Intel will lose money on these forward-priced early chips.

Intel will need to absorb these negative margins to scale volume and move down the cost curve.

Intel must also absorb depreciation expenses from low-capacity utilization during this time. It may even need to subsidize potential customers' NRE to convince them to use IFS as a second source.

The ideal strategy for IFS is to run down the cost curve and fill plants quickly. However, accelerating this process significantly increases quarterly cash burn due to the cumulative per-chip losses.

It’s already questionable whether Intel can sustain the $100B+ of CapEx as the price-of-entry to play the game; they surely can’t afford to forward price and scale quickly.

What options does a company in such a challenging position have?

Companies investing heavily in infrastructure—factories, R&D, and supply chains—often rely on external capital to bridge the financial gap until production scales and unit costs decline.

For example, venture capitalists and the government’s $7500 EV rebate supported Tesla starting in 2009 when the company incurred losses on every car sold. Investors and taxpayers covered Tesla’s expenses, and it worked. Tesla reached economies of scale and became profitable. It was also a great deal for Tesla’s venture investors, who were handsomely rewarded for taking on significant risk during the unprofitable early scaling phase.

This is the path forward for Intel Foundry.

IFS needs the ability to forward price competitively while it pursues the volume needed to move down the cost curve. This requires patient and abundant capital. But public markets are not patient.

This path requires a private Intel Foundry.

Intel must split into a fabless Intel Product company (remaining public as INTC) and a private Intel Foundry.

Capital should come from private markets, such as private equity, supported by government loans (including utilizing some of the $75 billion allocated through the Chips Act) and an equity kicker tied to a future public offering of Intel Foundry Services.

The investment will be significant. A private Intel Foundry take-off could require several tens of billions of dollars of runway. Only deep analysis with Intel can reveal the amount truly needed.

This amount might sound outlandish, but there is precedence. Fifteen years ago, GM raised ~$50B by selling a 61% equity stake to the US government; with inflation, that $50B is equivalent to roughly $73B in today’s dollars11. Bank of America issued preferred stock with warrants to the government in return for $45B of investment, which is ~$66B in today’s dollars.12

And don’t forget: it’s imperative for a secure democratic future. As highlighted in a recent CSIS report,

If the Big Three automakers and major U.S. financial institutions were deemed “too big to fail” in 2008, Intel can be similarly considered “too important to fail” in today’s increasingly perilous geopolitical environment.

An influx of capital will allow Intel Foundry Services to focus solely on crucial milestones:

timely delivery of 18A to gain customer confidence

using 18A success to win long-term partnerships (14A and beyond)

leveraging customer retention to ensure a faster and more profitable 14A ramp

These milestones pave the way for an eventual IFS public offering, demonstrating how government-backed funding can drive sustained economic and defense capabilities.

This also creates a path to a rewarding exit for Intel's private investors.

In conclusion, sustainable national security and strong deterrence amid geopolitical competition require American-owned, leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing on U.S. soil. A private Intel Foundry, enabled by significant public and private investment, offers the most viable path forward.

Thanks to Mark Rosenblatt for co-authoring this post with me.

https://moorinsightsstrategy.com/research-notes/research-note-intel-foundrys-once-lofty-goals-now-appear-in-sight/#:~:text=Intel's%20Five%20Nodes%20in%20Four,the%20Intel%2018A%20process%20node.

https://www.thewirechina.com/2024/10/27/intel-gets-caught-up-in-the-u-s-china-rivalry/