Right Systems for Agentic Workloads

Why Etched and MatX may be better positioned than Cerebras and Groq for long-context coding agents.

Back in October, I argued that AI labs and hyperscalers should run a portfolio of inference systems, each tuned to a specific class of work. I called it right-sized AI infrastructure. This week, Sachin Katti used nearly identical language when describing OpenAI’s parternship with Cerebras:

“OpenAI’s compute strategy is to build a resilient portfolio that matches the right systems to the right workloads.”

Right systems to the right workloads. Right on.

Katti continued:

“Cerebras adds a dedicated low-latency inference solution to our platform. That means faster responses, more natural interactions, and a stronger foundation to scale real-time AI to many more people”

Yep. Some workloads demand systems tuned for hyperspeed, which argues for adding a dedicated SKU to the portfolio. That was exactly the case we made for the Nvidia–Groq tie-up, and Jensen Huang has said as much publicly on CNBC.

Sam Altman, meanwhile, has been very explicit about what he wants next: really fast code-generation workflows.

Makes sense in light of Claude Code capturing hearts everywhere.

Most pre-GPT accelerators are best suited to fast, stateless inference for workloads that need minimal time-to-first-token. But real-time coding workflows require more than a small model and a short prompt. It’s more of an agentic inference loop, where the model runs continuously, accumulates context, and must retain and revisit a growing working set. Speed matters, but persistent, low-latency access to state matters just as much.

Cerebras and Groq ship without HBM. Can either support low-latency AI coding agents once context grows and must be repeatedly accessed? If so, this will become a defining use case for hyperspeed inference hardware.

Let’s see if these pre-GPT AI accelerators can handle context memory as a first-class citizen. Then we’ll look at post-GPT AI accelerators.

Cerebras and Groq. Both Early. Both Fast. But Different

Both Cerebras and Groq were founded before the rise of GPT (in 2015 and 2016, respectively). Their architectures were locked in well before massive models and long-context workloads were a thing. In hindsight, some of those early design choices are now constraints. For example, (and as everyone knows), Groq chips have only 230 MB of on-chip SRAM and no HBM. As a result, it takes hundreds of interconnected chips to run even a single large language model, even more if you want headroom for context.

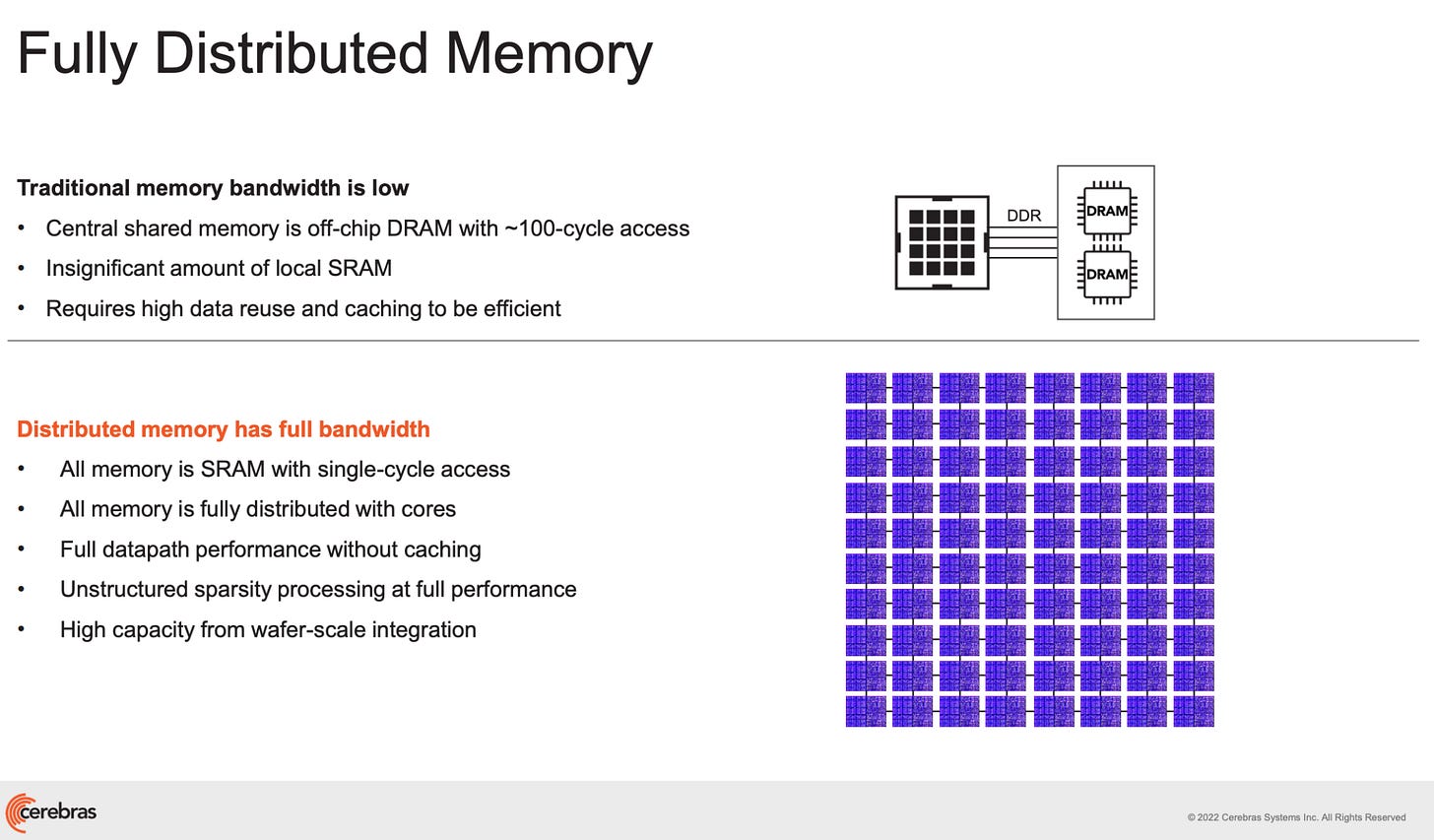

Cerebras, on the other hand, has “44 GB of on-chip SRAM and 21 petabytes per second of memory bandwidth” on its Wafer Scale Engine 3 (WSE-3).

Of course, that Cerebras “chip” is really a wafer full of dies, so it’s a bit apples-to-oranges to compare WSE-3 with a single Groq chip.

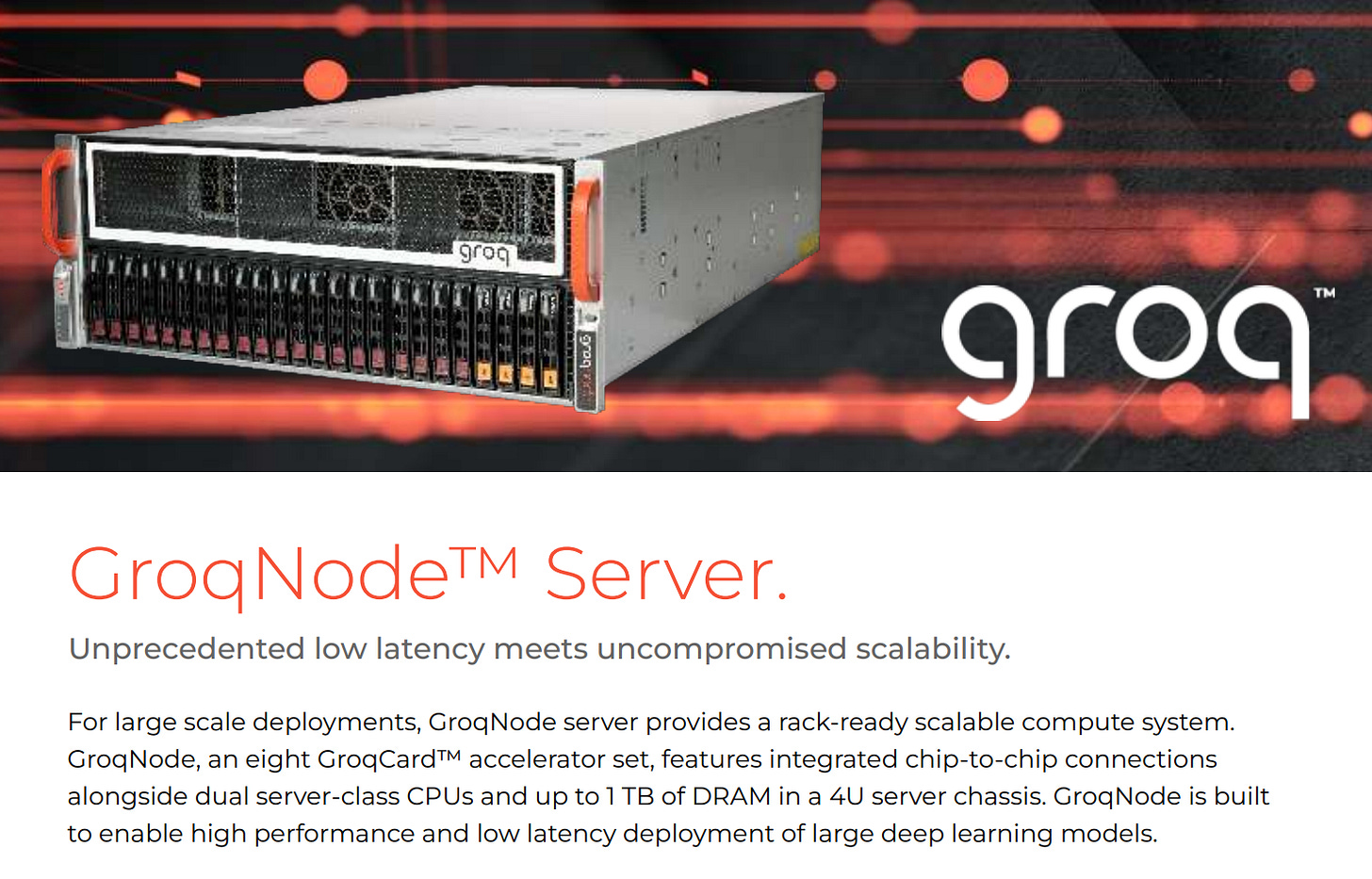

The right way to compare is at the systems level. Groq has one chip (LPU) per card, many cards in a server (8), and many servers in a rack (9):

And it takes many racks for Groq to run a small LLM. Per this example, it took 8 racks (576 LPUs) to run Llama2 70B.

1 LPU per card * 8 cards per node * 9 nodes per rack = 72 LPUs per rack.

8 racks * 72 LPUs/rack = 576 LPUs.

That means 576 separate cards all talking to each other.

Even with Groq’s RealScale optical fabric, the system can only connect 264 chips directly before it has to introduce switches, which add extra hops and latency.

The Next Platform: A pod of its current generation of GroqChips has an optical interconnect that can scale across 264 chips, and if you put a switch between pods, you can scale further but you get the extra hop across the switch jumping between pods, which adds latency. In the next generation of the GroqRack clusters, the system will scale across 4,128 GroqChips on a single fabric, but that is not ready for market just yet, according to Ross. Groq’s next-generation GroqChip, due in 2025, etched in Samsung’s 4 nanometer processes, will scale even further than this thanks to the process shrink, the architectural enhancements, and the advancements in the fabric on the chips.

Groq’s v1 clearly has a ceiling; simply scaling to more chips to increase available memory has limits.

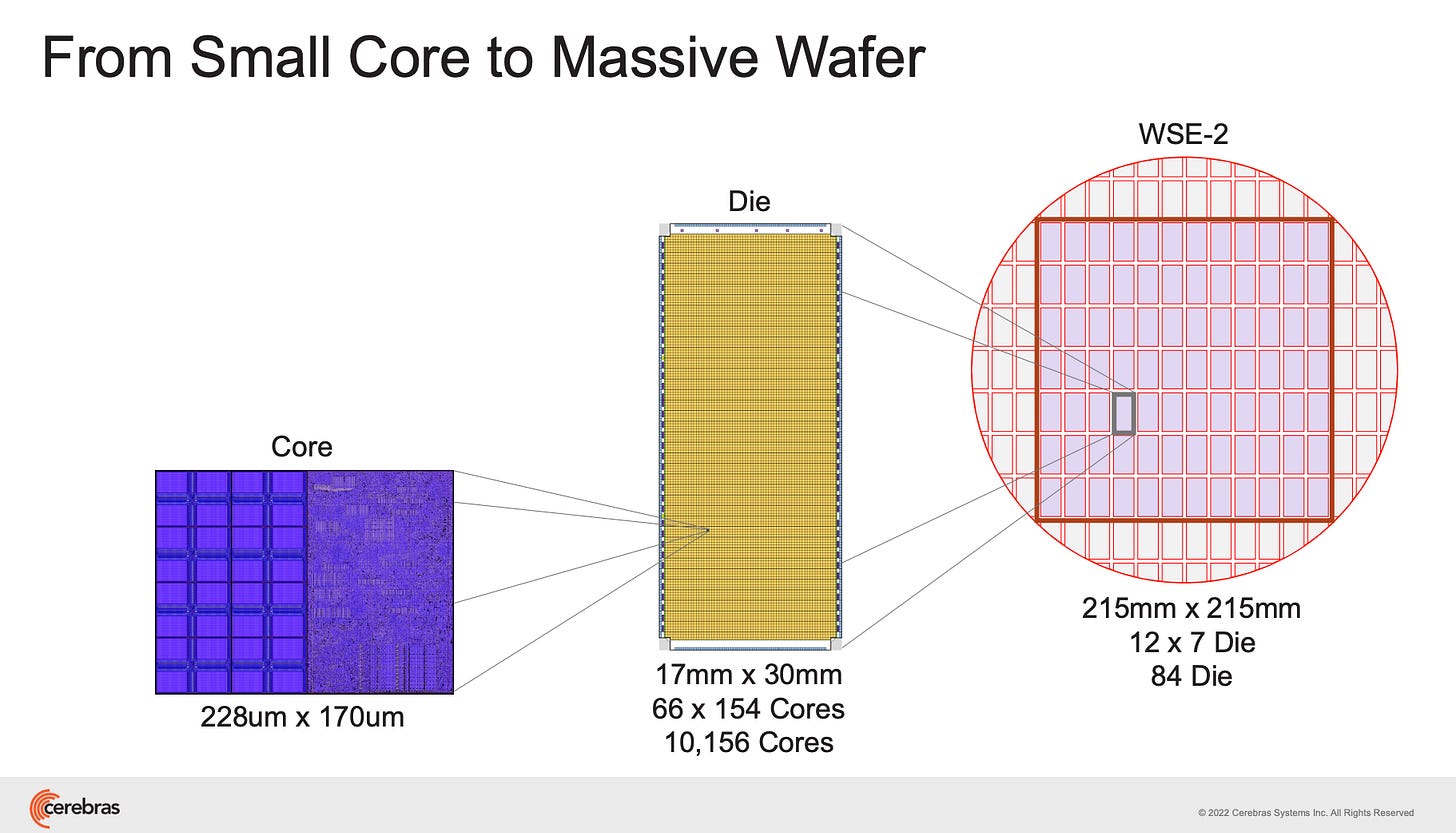

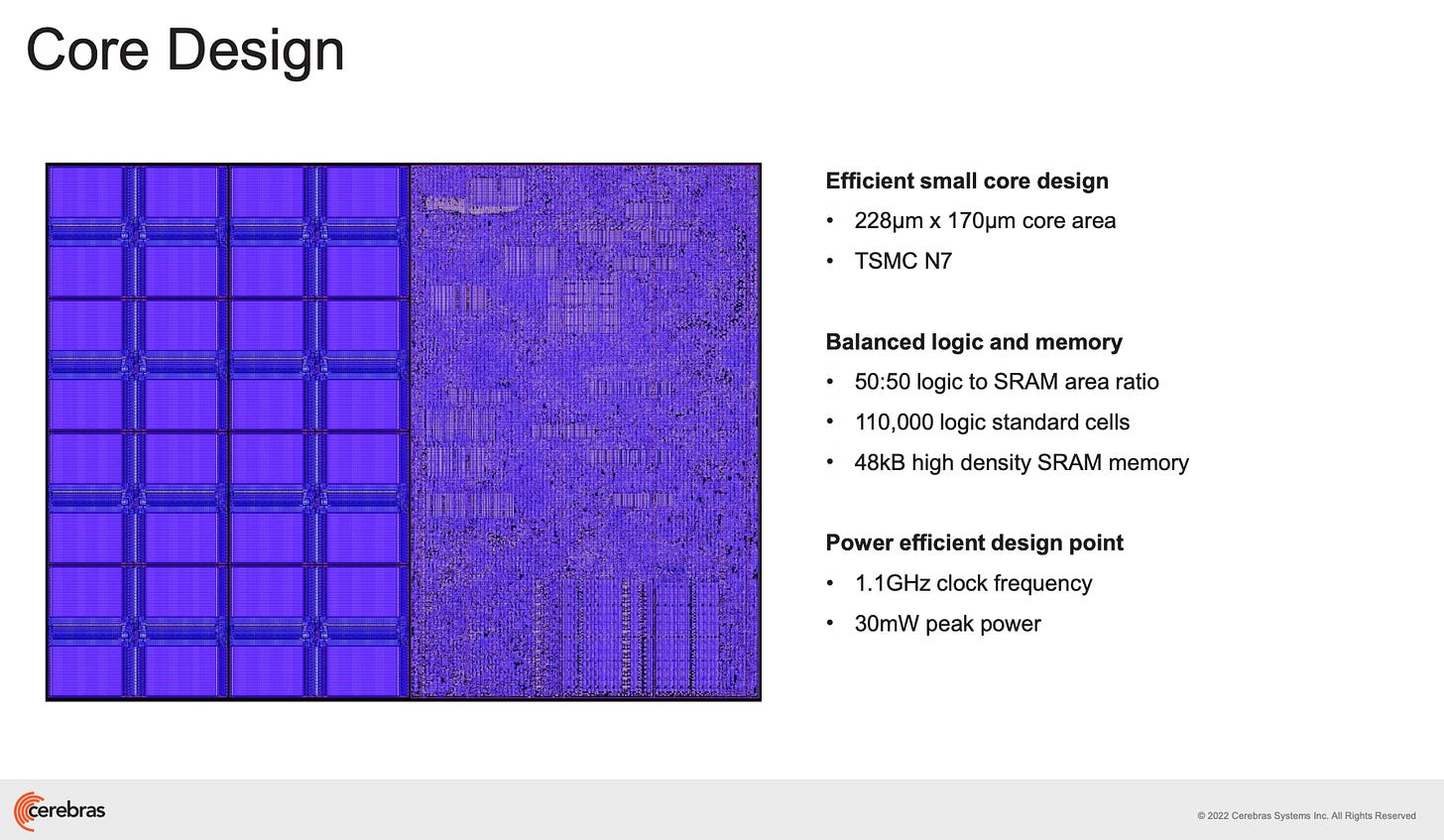

Cerebras, by contrast, is a single, wafer-scale processor with many die integrated into a single piece of silicon:

One WSE-3 wafer contains roughly a million compute cores, with redundancy allowing defective areas to be worked around:

Technically, it sounds like they pattern 1,000,000 cores and then yield harvest 900K of them. So at least 900K working cores. Highly recommend this video to learn more:

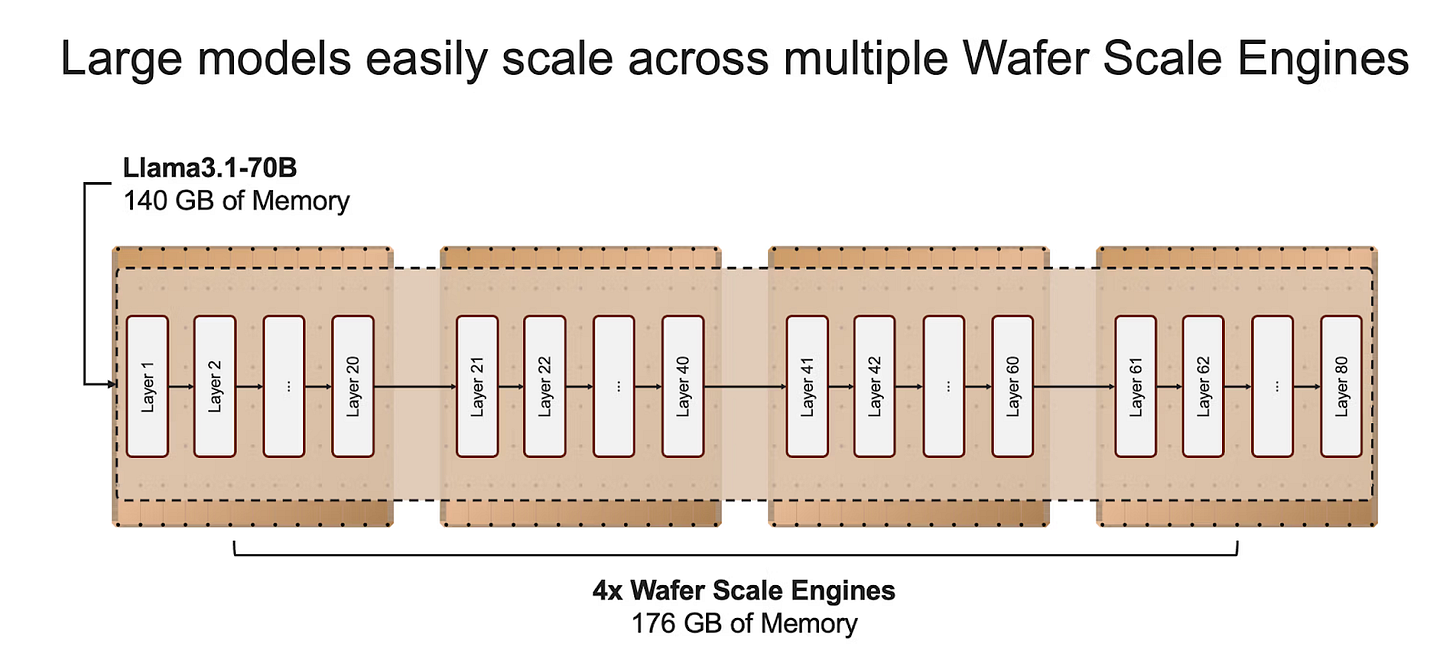

Because Cerebras has 44GB of SRAM per WSE, it only takes 4 wafers to store Llama 70B weights:

With Cerebras, much more communication occurs on the wafer, avoiding the latency and bottlenecks of off-chip networking. Moreover, SRAM are distributed amongst the die to keep memory as local as possible:

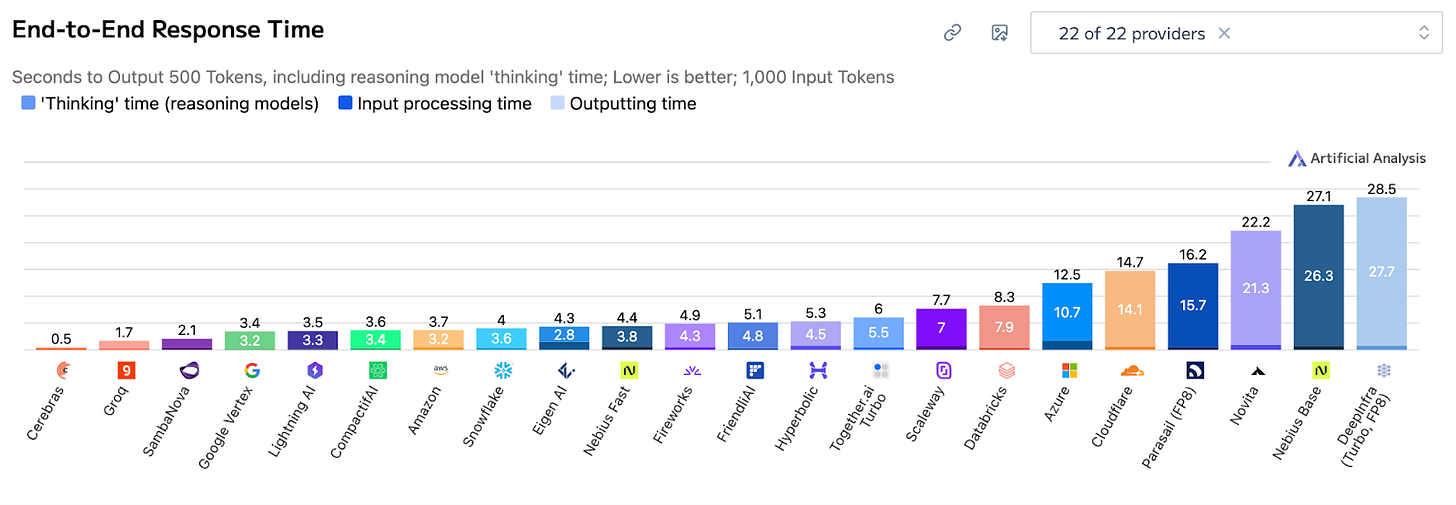

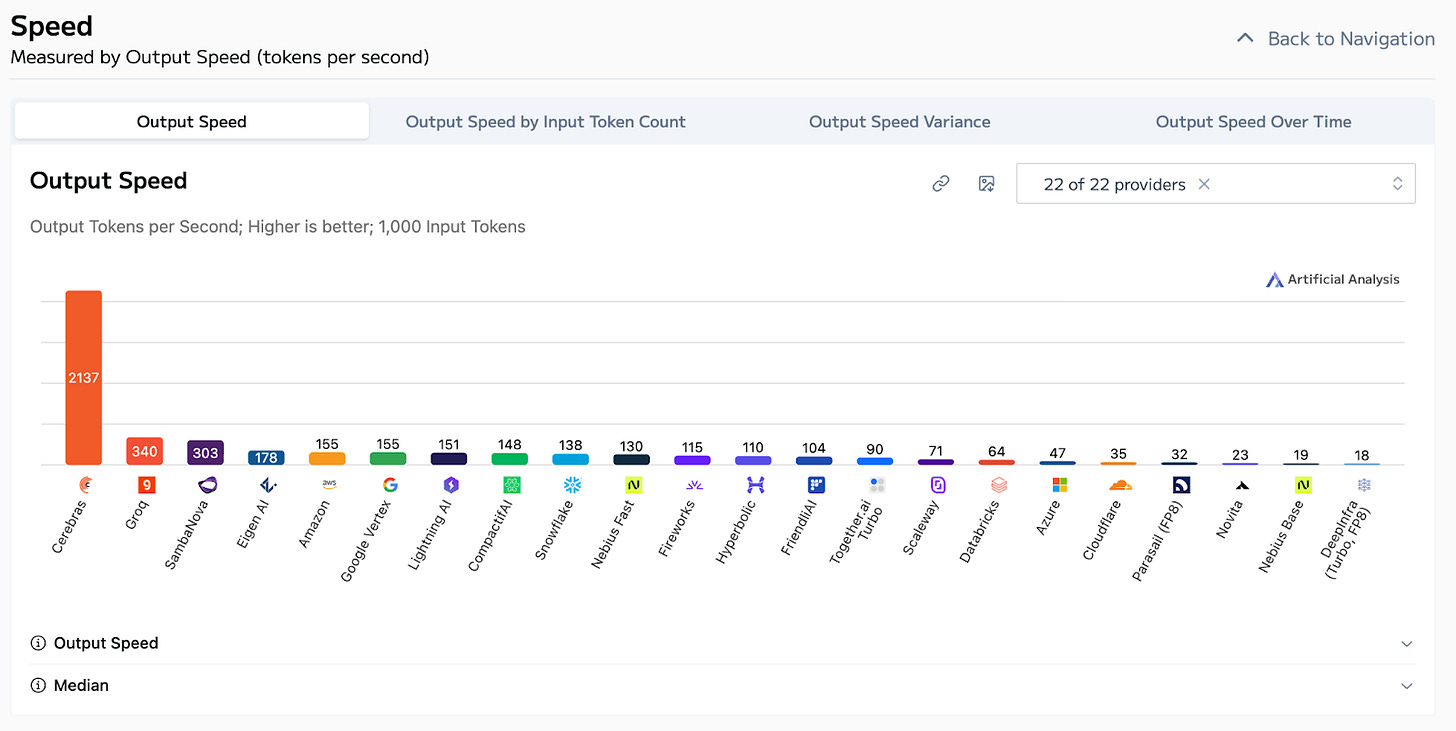

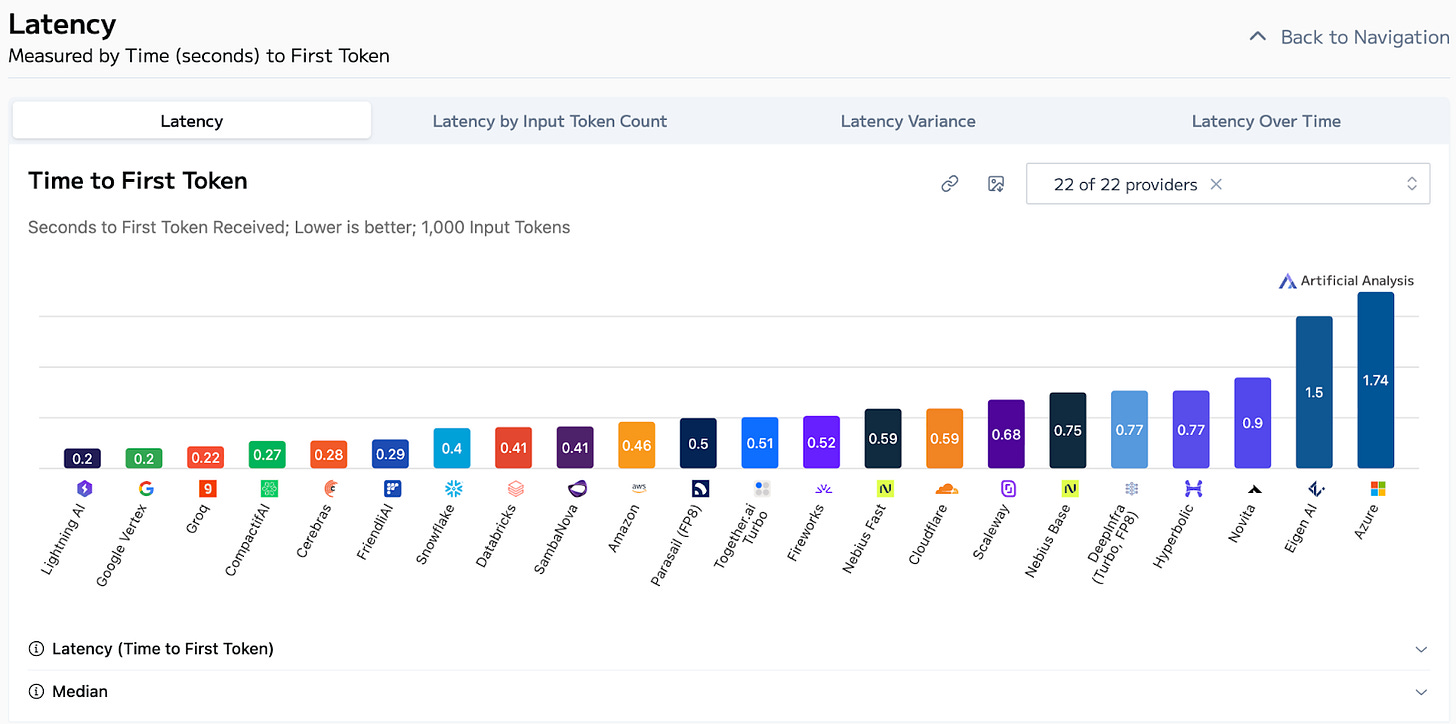

Hence, Cerebras can unlock the best end-to-end response time, massive tokens per second, and very low time-to-first-token:

Both Cerebras and Groq are undeniably fast.

But can Cerebras speed up Codex as Sam hopes? Speed alone isn’t the whole story. Context management matters!

Cerebras + Codex in a Ralph Loop

Recall that I said it would take 4 WSE to hold the weights for Llama 70B. But inference systems must hold onto more than just the weights.

At runtime, an inference system also needs memory for intermediate activations and scratch space, attention computations, and most importantly, KV cache, which stores everything the model remembers about the conversation so far. Explainer from Devansh:

KV Cache: The technical term for “State.” When a model reads your prompt, it calculates a massive set of Key-Value pairs representing the relationships between words.

Think of the KV Cache as the transcript of the model’s understanding. If you keep the transcript, the model can answer follow-up questions instantly. If you delete it, the model must re-read the entire book to understand the context again.

As the conversation or task grows, the KV cache grows with it. For long-running tasks, the KV cache can explode. And recall how important context memory management is to the user experience and tokenomics, per Vik’s Newsletter:

Due to the way Attention is calculated in an LLM, context is closely linked to the KV$ which grows linearly with context length. If it grows too large, it must either be moved to a higher capacity (but slower) storage device, or somehow compacted in place. If the KV$ retrieval from storage is too slow, Time To First Token (TTFT) is impacted greatly, and it is faster to just recompute the KV matrices again at the cost of higher GPU utilization. If KV$ is compressed, it loses accuracy and adds error. In effect, KV$ handling affects overall token throughput and ultimately, inference tokenomics.

Now granted, for simple “write a function” or “explain this error” tasks, modest context is fine. But large context becomes important when the job requires repository grounding and long-running agent loops. Think “make a correct change in a real codebase”.

After all, the quality of vibe coding has skyrocketed lately with the addition what folks playfully call the Ralph Wiggum Loop. The model finishes, then immediately asks itself if the code can be improved. Tests fail? Fix it. Tests fail again? Fix it again.

Each iteration adds more context. Over time, the active context can grow to tens or hundreds of thousands of tokens, and they must remain accessible if you want fast responses.

That’s exactly the problem Nvidia’s Context Memory Storage Platform (ICMS) is designed to solve, by pushing context into a tiered memory system without destroying latency. Recommend Vik’s article on this, has helpful illustrations behind the paywall.

Well, Cerebras’s speed should be awesome for the Codex in a Ralph Loop experience, but only if it can handle long context memory too.

Can Cerebras offload this KV cache if it’s too big to fit on the SRAM?

They haven’t explicitly spoken to this, but they might already have a lot of the pieces they need. What I found: Cerebras has a product called MemoryX, which it uses to offload model weights during training. From a blog post back in Mar 2024:

Unlike GPUs, Cerebras Wafer Scale Clusters de-couple compute and memory components, allowing us to easily scale up memory capacity in our MemoryX units. Cerebras CS-2 clusters supported 1.5TB and 12TB MemoryX units. With the CS-3, we are dramatically increasing the MemoryX options to include 24TB and 36TB SKUs for enterprise customers and 120TB, and 1,200 TB options for hyperscalers. The 1,200 TB configuration is capable of storing models with 24 trillion parameters – paving the way for next generation models an order of magnitude larger than GPT-4 and Gemini.

A single CS-3 can be paired with a single 1,200 TB MemoryX unit, meaning a single CS-3 rack can store more model parameters than a 10,000 node GPU cluster. This lets a single ML engineer develop and debug trillion parameter models on one machine, an unheard of feat in GPU land.

Cerebras has primitives for offloading data (model weights) and streaming it back to the compute when needed. In theory, if you squint, managing KV cache is similar — offload data (KV Cache) to a memory server (DRAM + flash) until you need it.

This whitepaper confirms MemoryX uses a tiered memory storage system:

Internally, the MemoryX architecture uses both DRAM and flash storage in a hybrid fashion to achieve both high performance and high capacity.

So can Cerebras eloquently handle long context and KV$ management? I bet they are working on it. Cerebras folks feel free to reach out and enlighten me!

What about Groq? They have never mentioned any sort of “offload KV cache to memory server” approach… but we don’t know anything about Groq’s roadmap, plus they work for Nvidia now… so anything is possible :) But with the v1 systems, right now it doesn’t seem like it.

PreGPT vs PostGPT AI accelerators

Groq and Cerebras are pre-GPT accelerator companies that avoided HBM in favor of large pools of fast local SRAM. To their credit, they survived long enough to find hyperspeed inference workloads where those choices shine. And maybe they can tack on a memory server to overcome memory constraints.

On the other hand, I’ve long been bullish on post-GPT AI accelerator startups. From Nov 2024’s MatX Prediction,

Pre-ChatGPT companies built silicon first and then went to find customers and problems to solve. MatX, like Etched, designed their chips after transformer-based LLMs took off.

What happens when you can design on day one for the obvious workload (LLMs) and customers with insatiable demand (hyperscalers / AI labs) ?

Well,