GPU Networking, Part 4: Year End Wrap

Where Scale-Up, Scale-Out, and Scale-Across Stand at Year End 2025

As 2025 comes to a close, let’s check in on the current state of the AI networking ecosystem. We’ll touch on Nvidia, Broadcom, Marvell, AMD, Arista, Cisco, Astera Labs, Credo. Can’t get to everyone, so we’ll hit on more names next year (Ayar Labs, Coherent, Lumentum, etc).

We’ll look at NVLink vs UALink vs ESUN. And I’ll explain the rationale behind UALoE.

We’ll talk optical, AECs, and copper.

It’ll be comprehensive. 6000 or so words, with 70% behind the paywall since I spent a really long time on this :)

I’ll even toss in some related sell-side commentary.

But first, a quick refresher on scale-up, scale-out, and scale-across. There’s still some confusion out there.

Scale Up, Scale Out, Scale Across

AI networking is mostly about moving data and coordinating work. The extremely parallel number crunchers (GPUs/XPUs) need to be fed data on time and in the right order.

Scale-up, scale-out, and scale-across are three architectural approaches to transmitting that information, each with very different design tradeoffs.

It’s important to understand the nuance of scale-up, so let’s start there.

BTW: I’ll use GPU and XPU interchangeably as a shorthand for AI accelerator.

Scale Up

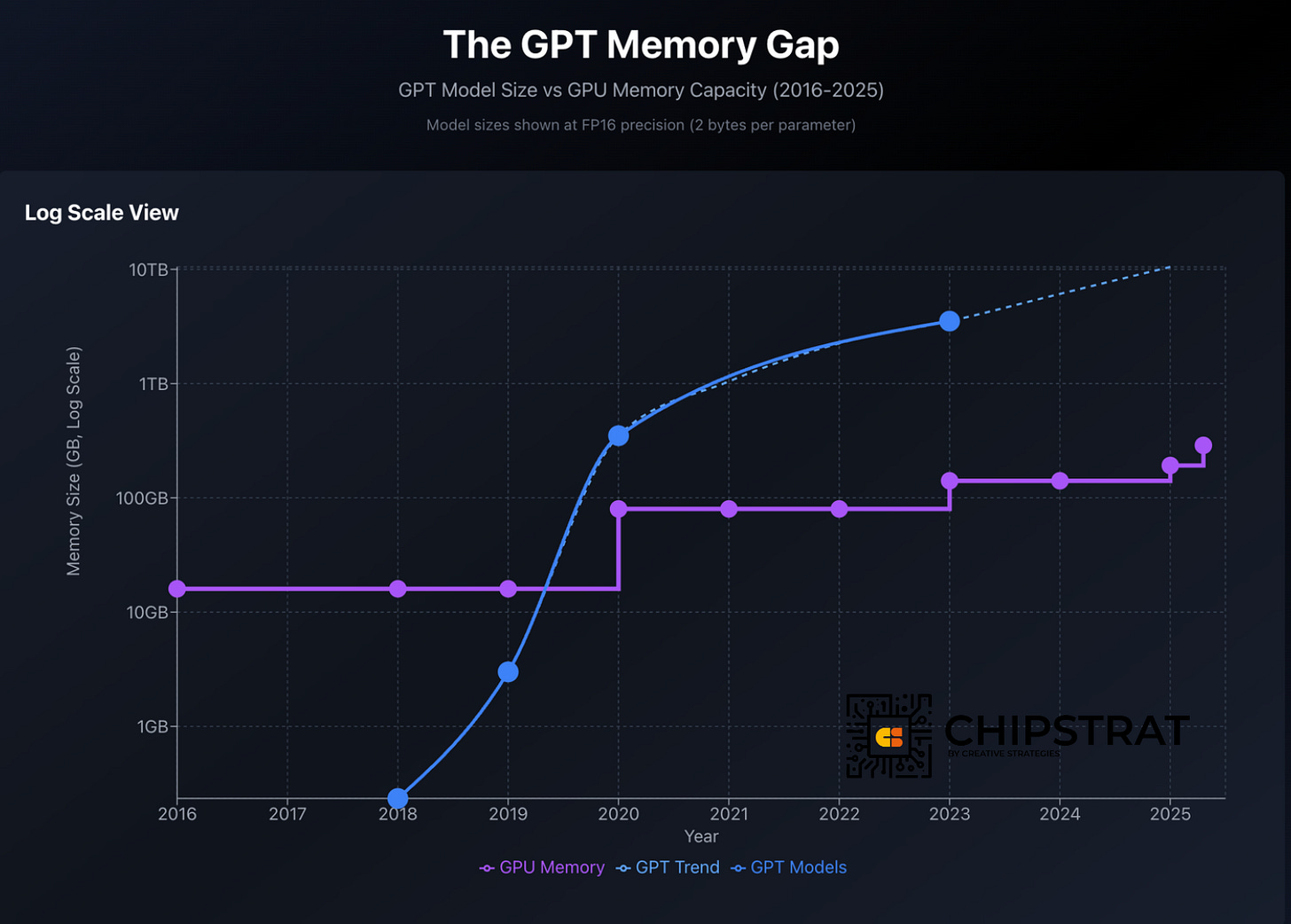

GPUs have a fixed amount of high-bandwidth memory (HBM) per chip; that capacity is increasing over time, but it can’t keep up with the rapid increase in LLM size. It’s been a long time since frontier models fit into the memory of a single chip:

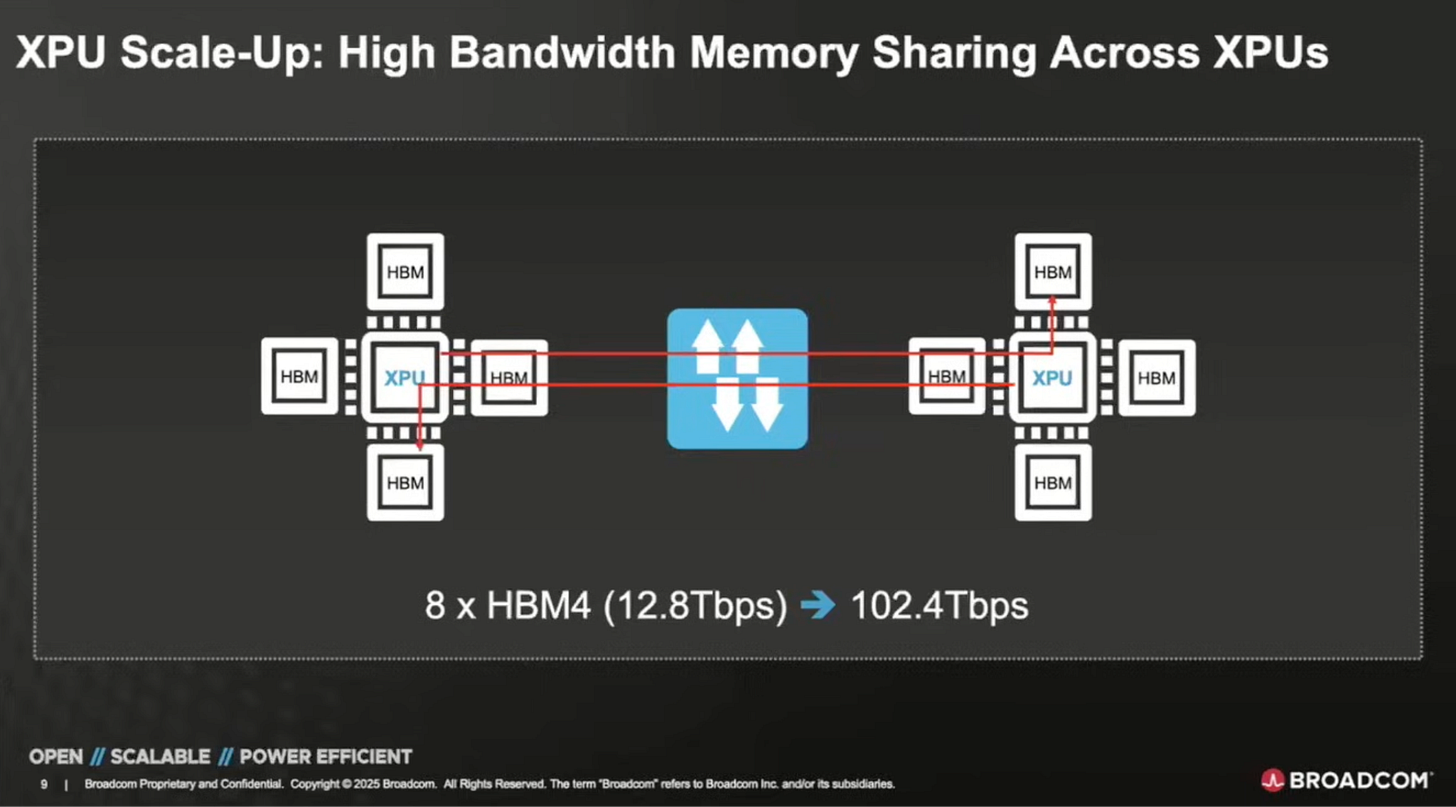

Once a model no longer fits in a single GPU’s HBM, the accelerator must fetch portions of the model from elsewhere. As there’s no nearby shared pool of HBM today, “elsewhere” means accessing HBM attached to other accelerators over a network, which is slower and less predictable than local memory.

But what if fetching memory from “elsewhere” could be made fast enough that the accelerator barely notices? That’s the motivation behind scale-up networking!

Scale-up pools memory across multiple GPUs so they behave like one larger logical device with a much bigger effective HBM footprint:

Pulling this illusion of locality off requires really fast interconnects; the goal is to make remote HBM feel as close to local memory as possible.

When this works, multiple accelerators behave like one big GPU with a lot of memory. You might hear this called a “single logical compute domain”. To the software, it feels like it's running on a single large GPU with a lot of local HBM, so the programmer doesn’t need to manage GPUs or explicitly track where data lives.

Low-latency networking is necessary for scale-up, but achieving that “single big GPU” illusion also depends on the compiler and runtime coordinating how work and data are managed. Which means another benefit here is that compute scales up along with memory, too. That’s why Jensen frames NVL72 as one huge supercomputer:

Jensen Huang: The amount of computation we need is really quite incredible. [NVL72] is basically one giant chip.

If we had to build this as one chip, obviously this would be the size of a wafer. But this doesn’t include the impact of yield—it would have to be probably three or four times the size.

What We Actually Have:

72 Blackwell GPUs (144 dies)

1.4 exaFLOPS of AI floating-point performance.

For context: The world’s largest supercomputer only recently achieved an exaFLOP. This entire room-sized supercomputer only recently achieved that. This single system is 1.4 exaFLOPS.14 terabytes of memory

1.2 petabytes per second memory bandwidth

That’s basically the entire internet traffic that’s happening right now. The entire world’s internet traffic is being processed across these chips.

130 trillion transistors in total

2,592 CPU cores

Plus a whole bunch of networking!

And this is the miracle—this is the miracle of the Blackwell system.

Scale-up networking is a key enabler of Nvidia’s miracle.

As we’ll discuss later, scale-up represents a large TAM opportunity in 2026, since most training and inference communication occurs locally rather than across the broader network:

Nvidia’s NVLink is the predominant scale-up technology, yet 2026 is the first year credible alternative fabrics and switches reach the market. We’ll dive into protocol wars down below.

Physical Boundaries

A real quick clarification: a common misconception is that scale-up is “within a rack” and scale-out is “rack-to-rack”. Yes, in practice that’s what we see, but it is not a technical limitation!

Of course, on the one hand, you’re not wrong. Patrick Kennedy’s videos show the progression to rack scale. First, the Hopper generation tightly couples eight GPUs within a single server:

And now Blackwell NVL72 extends this model to the whole rack, logically connecting six-dozen GPUs into a single scale-up domain (see ~10:30):

Nvidia plans to push this even further with Rubin NVL144 and then NVL576! 576!

So it definitely feels like “scale up” means “within a rack”. But scale-up is not defined by rack boundaries! Accelerators can be tightly coupled across adjacent racks and still behave as a scale-up system as long as latency remains low and memory-style access is preserved.

So two GPUs, each in a neighboring rack, could be connected in a scale-up fashion and part of the “one large GPU” illusion.

Scale-Out

Scaling up increases the effective size of a system, allowing more work to be done in roughly the same amount of time. But the scale-up domain is finite. What happens when you want to do even more simultaneous work than can be supported by a single domain, for example beyond the 72 GPUs in NVL72?

You have to scale out.

So if scaling up is adding more GPUs to a single domain, visualized like this:

Then scaling out is adding additional independent domains to the system:

There’s local coordination within a scale-up domain, and global coordination across the scaled-out system.

Here’s an analogy.

Farming Analogy (Scale Up vs Scale Out)

Say you’re a farmer. Some nasty weather is forecasted for the next week, so you want to quickly harvest the rest of your fields faster than usual. You need to get more work done in the same amount of time.

One option is to add another combine harvester to the same field. Scale up.

If a single combine takes eight hours to clear the field, running two in parallel might cut that to roughly four hours. You are accelerating completion of one shared job. This is analogous to scaling up. Multiple machines work together on the same problem:

But doing this two combine dance efficiently requires fine-grained coordination: they need to plan paths with the other machine in mind, and ensure support equipment like grain carts can move without interrupting harvesting. Notice in the image how one combine clears a path so the grain cart can service the other without slowing it down.

Communication between combines in the same field can be very fast. Line-of-sight hand gestures when possible are instantaneous. You turn and go ahead, I’m getting out to take a leak!

Call over the CB radio and they’ll basicaly hear it instantly too.

Scale-up AI systems behave the same way. Multiple GPUs collaborate closely on a single local piece of the workload, requiring frequent coordination via low-latency communication.

So back to the farming example. How far can you scale this up?

As you can imagine, beyond a certain number of combines in one field, coordination overhead dominates and productivity stops improving. So if another friend arrives with their own combine, the better option is to send them to a different field.

That is analogous to scaling out. The shared goal is to harvest all fields, but each field is worked independently, with only high-level coordination. I’ll be done by 2pm, what field should I tackle next?

Scale out communication is slower. The other field might be twenty miles away, so coordination happens over a phone call rather than hand signals or CB. Still fast of course, but no longer instantaneous as someone’s gotta grab the phone and swipe to answer.

So the farming analogy can be illustrated like this:

OK, hopefully scale up and scale out is pretty clear by now. Thanks for your patience with my analogy :)

For more on scaling out, check out part 3 of this series:

Scale Across

Scaling out works well. Add more racks in that datacenter! Add another datacenter hall to that campus! Go go go!

But what happens when you hit a local constraint, like you’ve used up all the power you have in that location? At that point, the obvious question is whether you can tap power somewhere nearby. If two data center campuses are only tens of miles apart, communication between them is still pretty fast over fiber. Fiber moves data at close to the speed of light…

Can those physically separate data centers still coordinate on a single massive training run? Yep!

This year Nvidia introduced a new term for scaling out over physically separate datacenter campuses: scale across.

Scale across means scaling a single AI workload across multiple, geographically separate data center campuses.

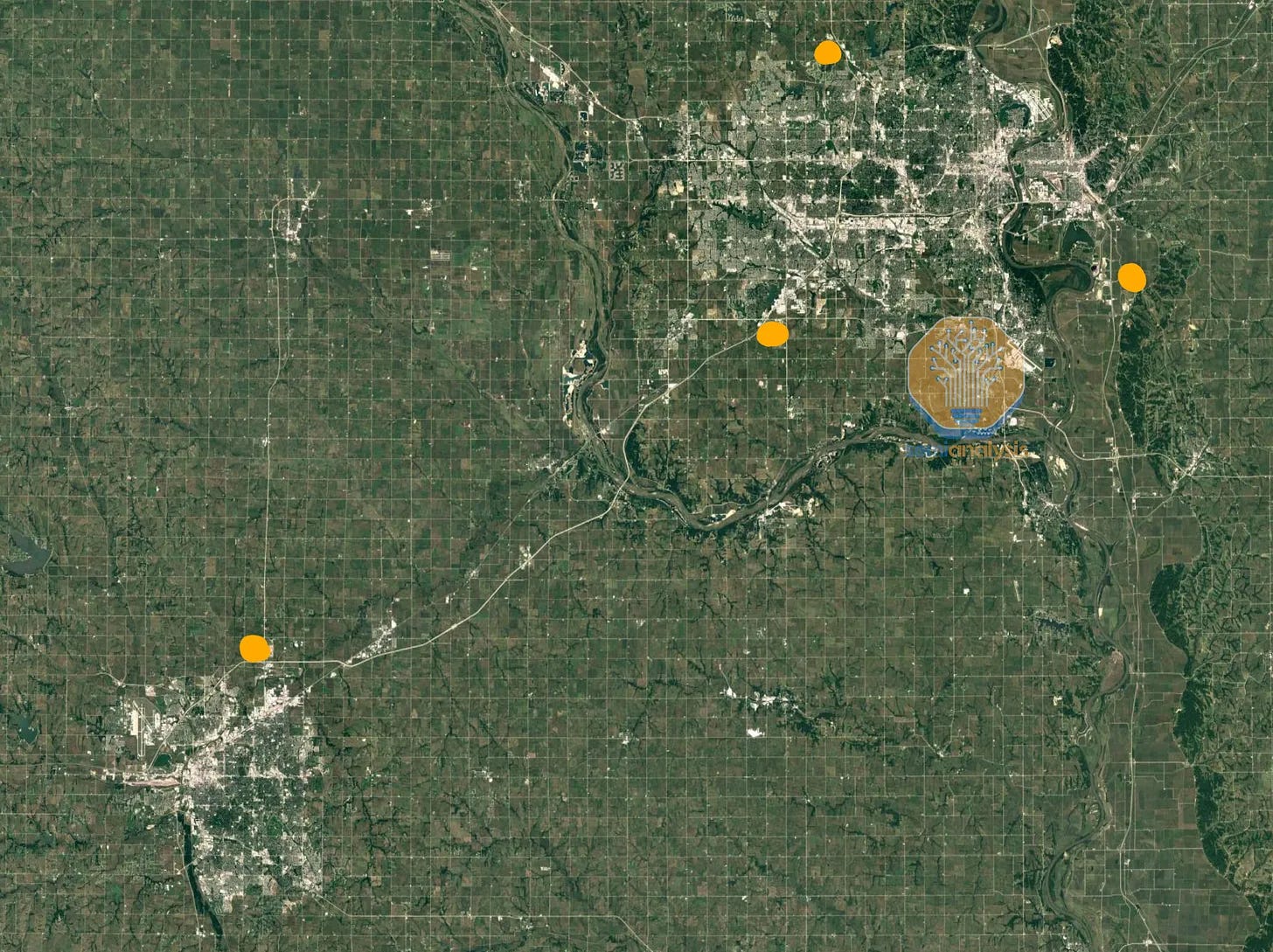

SemiAnalysis illustrates an example from Google, where isolated campuses will be connected for massive training runs:

There are three sites ~15 miles from each other, (Council Bluffs, Omaha, and Papillon Iowa), and another site ~50 miles away in Lincoln Nebraska. The Papillion campus shown below adds >250MW of capacity to Google’s operations around Omaha and Council Bluffs, which combined with the above totals north of 500MW of capacity in 2023, of which a large portion is allocated to TPUs. The other two sites are not as large yet but are ramping up fast: combining all four campuses will form a GW-scale AI training cluster by 2026.

Belaboring the analogy, the same scale-across pattern shows up in farming. Entrepreneurial farmers that want to keep growing the business eventually run into local land constraints since farmland rarely changes hands. Honestly, it’s usually just when someone dies or they don’t have family to keep the operation going. Most farmers don’t want to retire. Many such examples like this combine-driving 90-year-old grandma still at the helm.

When expansion at home is no longer possible, the farmer might buy land several hours away; e.g. Iowa farmers buying land in Missouri. They end up with an Iowa operation and a Missouri operation, each with its own local equipment and crews. The owner or manager is now coordinating at the highest level across state lines, while local crews deal with local logistics.

That is effectively scaling across. Physically separate operations are tied together into one managed system, once local expansion runs into hard physical limits.

Ok. Enough with the analogy and the basics. But wanted to make sure any newbies are 100% clear on scaling up, out, and across!

State of The Industry at Year End

Behind the paywall:

State of AI networking at year-end 2025. A structured check-in on how the ecosystem has evolved, what changed, and what matters heading into 2026.

Who we cover. NVIDIA, Broadcom, Marvell, AMD, Arista Networks, Cisco, Astera Labs, Credo.

Scale-up interconnects. Comparison of NVLink vs UALink vs ESUN, plus the architectural rationale behind UALoE.

Scale-out fabrics. How Spectrum-X compares with Ultra Ethernet, and where Arista and Cisco fit competitively.

Physical layer reality. Optical vs AECs vs copper, including Credo AECs relative to competing approaches and where each wins on power, reach, and reliability.

Primary research. Integrated sell-side commentary and lots of relevant conference conversation quotes

Depth and scope. ~6,000 words, deliberately comprehensive, designed as both a catch-up for late 2025 and a reference point for 2026 as scale-up, scale-out, and scale-across competition accelerates.