Anticipatory Intelligence and the Return of Windows

How Local Inference Could Revive Windows

At Microsoft Build this week, agentic AI stole the spotlight. But for me, an older story felt more important: Windows.

As I jogged along the Seattle waterfront each morning, I kept returning to the question Can Windows matter again?

I think it can.

To see why Windows can matter again, let’s first rewind and revisit how it became the integration layer, then lost that position in the shift to cloud and mobile, and why local AI creates a path to reclaim it.

The Unbundling of the Computing Stack

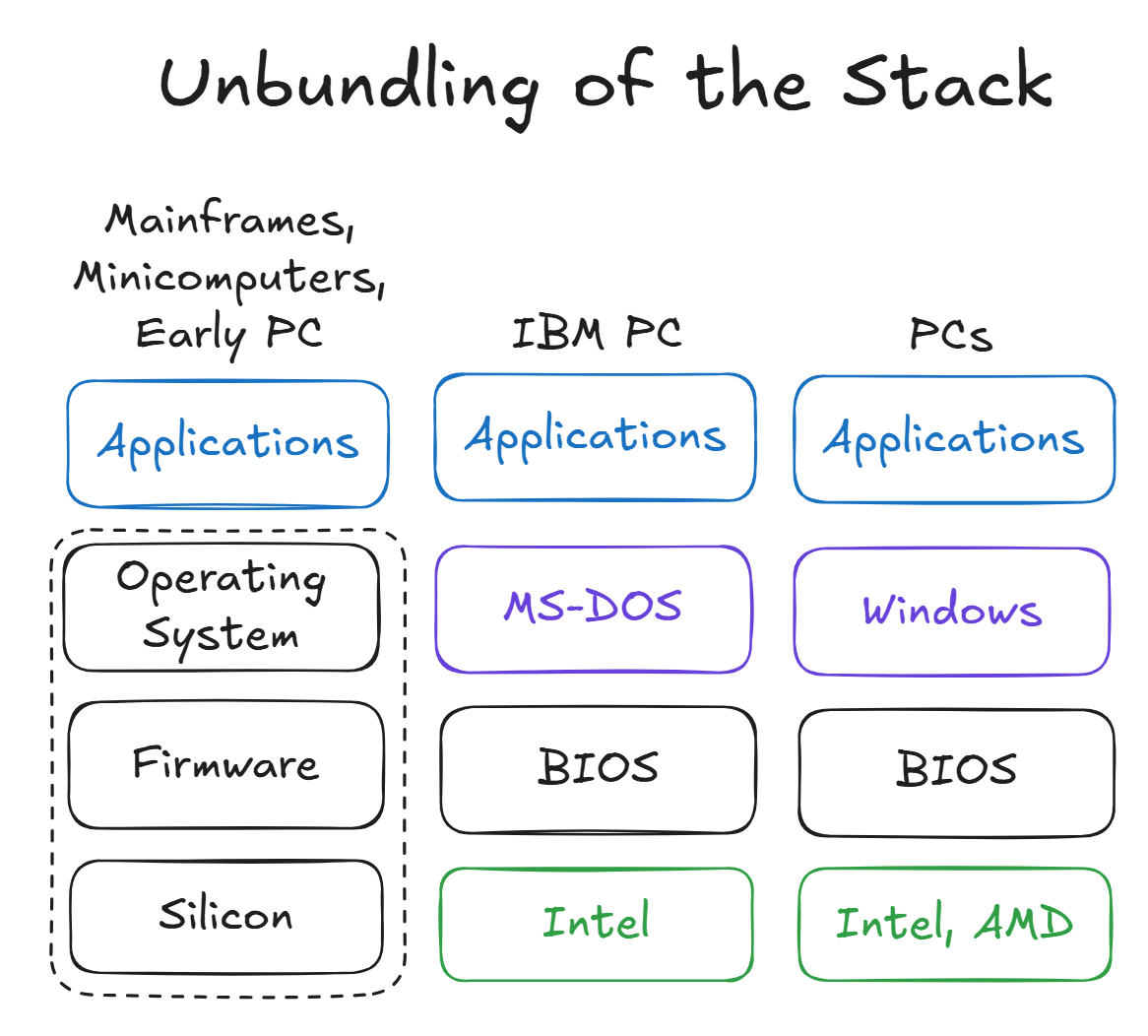

In the early days of computing, companies behind mainframes and minicomputers were vertically integrated. IBM, for example, designed and fabricated its own chips, built the hardware, wrote the operating system, and developed business software. The entire stack was in-house.

That model began to shift with the IBM PC. Although IBM assembled the system, it used off-the-shelf components; Intel made the CPU, and Microsoft supplied the MS-DOS operating system. Notably, Microsoft retained the rights to license MS-DOS to other OEMs.

The vertical integration model was unbundled when companies like Compaq successfully cloned the IBM PC BIOS. PC makers could now assemble machines from commodity parts and rely on MS-DOS (later Windows) as the software layer that made it all work together.

This changed the industry from vertically integrated giants to a horizontal ecosystem. Microsoft provided the OS, Intel (and later AMD) supplied CPUs, and OEMs like Compaq and Dell built the systems. Developers could write for Windows and reach millions of machines without worrying about hardware differences.

The OS became the platform.

This was the unbundling of the computing stack.

Wintel

This was also the beginning of the “Wintel” era. As the value chain unbundled, profits flowed to the new integration points. Microsoft controlled the developer ecosystem and user interface, and Intel dominated the compute layer. The profit margins accrued to Wintel. Despite assembling the final product, PC OEMs were largely interchangeable and locked in a margin race to the bottom.

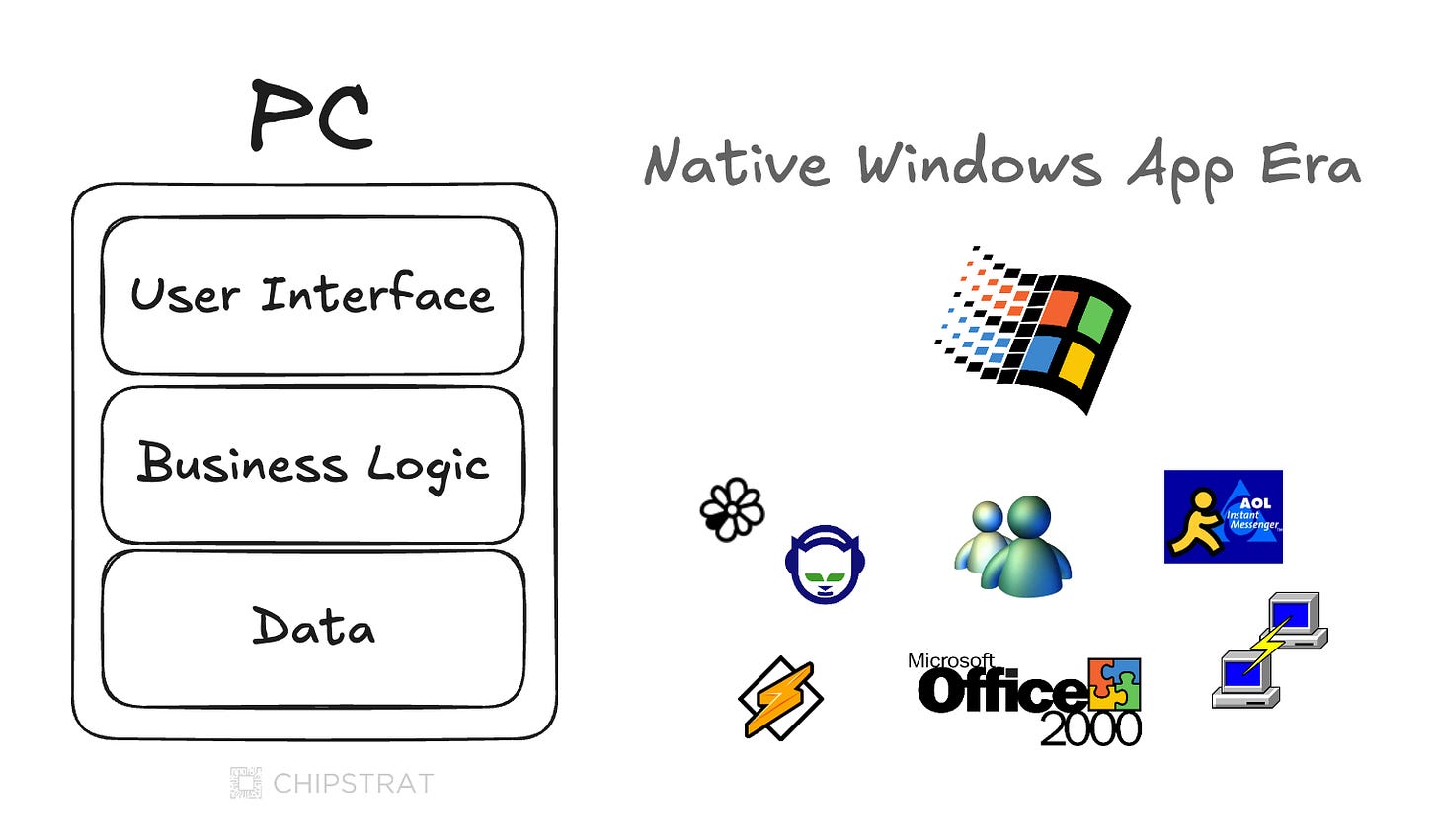

Desktop Apps

This was also the era of native Windows apps.

Windows wasn’t just an operating system, but was the entire app platform. Apps ran locally, and everything from the interface to the data lived inside the Windows runtime. If you were building software for the mass market, you were building for Windows.

This gave Microsoft immense leverage. It owned the full development stack, from the development environment (Visual Studio) to the APIs and even UI conventions. Porting to other platforms was painful for developers, and switching OSes was disorienting for users.

Thus, developers committed to the Windows ecosystem and enterprises built their workflows around Windows software. And Microsoft could extend its reach with first-party products like Internet Explorer and Office.

Mobile, Cloud, and Unbundling of the PC

But the rise of mobile and cloud broke that model.

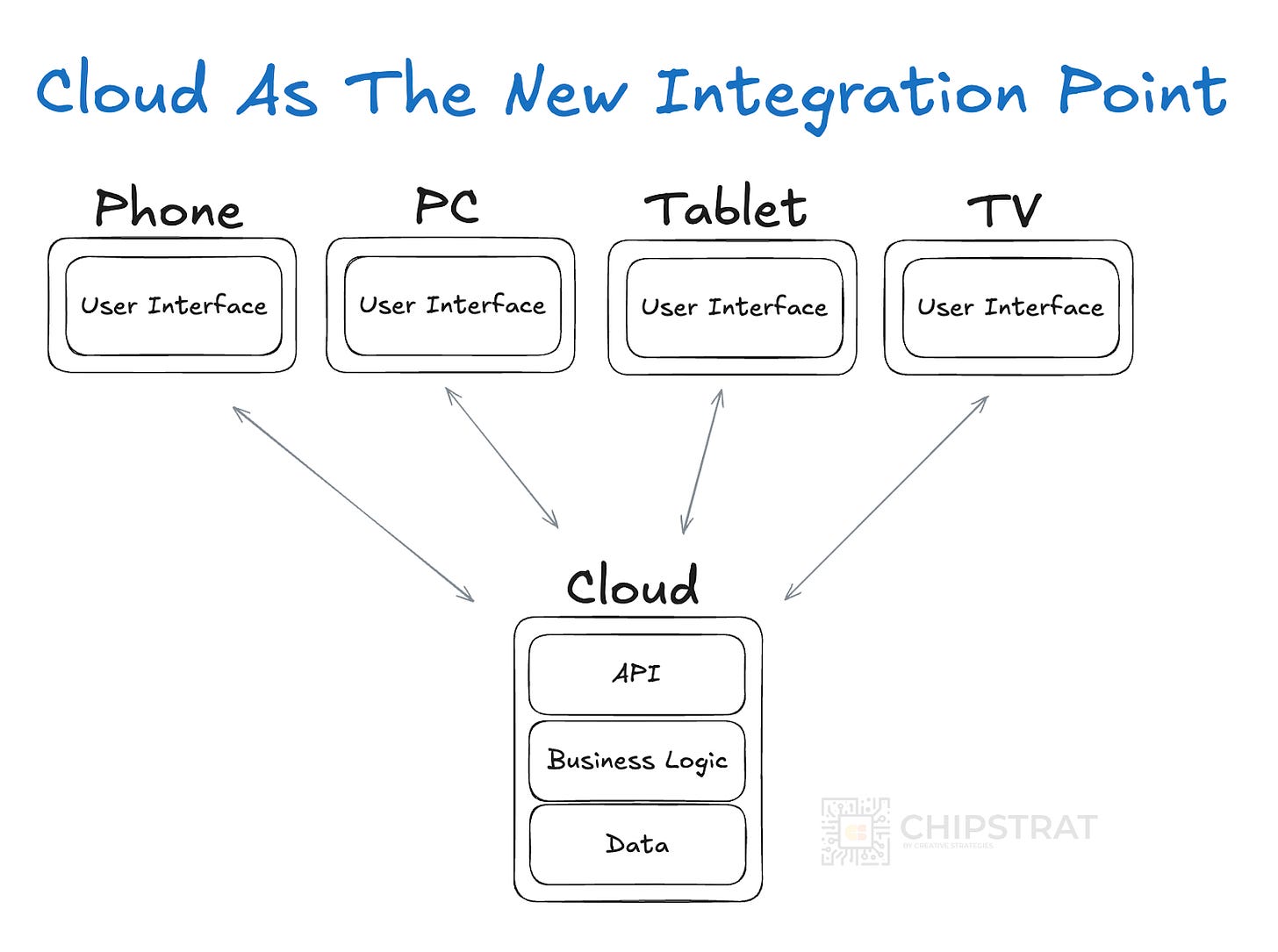

As smartphones and tablets spread, users began expecting their apps and data to work everywhere. Gmail users didn’t care whether they were on iOS, Android, macOS, or Windows, they just wanted their inbox to be available wherever and whenever.

Developers, in turn, could no longer write to a single OS and reach the entire market. They had to support every form factor and operating system.

At the same time, the rise of the cloud was making this portable experience possible. Developers could offload state and logic to the cloud so users could access their data from anywhere. Client apps retained the UI logic and made API calls to cloud APIs.

Phones, tablets, PCs, and TVs could all connect to this shared cloud backend as long as they had a data connection.

The cloud became the integration point. The PC was unbundled.

This shift reshaped Windows’ role. You no longer needed it to run your favorite app. You just needed a browser.

As cloud-first companies like Salesforce took off, the SaaS model became dominant. Enterprises adopted web-based tools. Users cared less about operating systems and more about services. You don’t think about what OS runs Spotify, Slack, or Zoom, but you simply expect them to work anywhere.

Windows apps didn’t disappear, but even native ones began to use cross-platform frameworks. For example, Spotify rewrote its desktop app using TypeScript, a superset of JavaScript.

Windows remained relevant for legacy systems, enterprise tools, and hardware integration. But it stopped being where the value was created. It faded from platform to plumbing.

Fortunately, Microsoft and Satya Nadella shifted to a “mobile-first, cloud-first world” and the Azure business has since taken off.

But…

And yet, at Microsoft Build this week, one thought kept returning: Windows can matter again.

If on-device AI unlocks new user experiences at the edge, developers will have real reasons to build client apps that tap into local models. Windows has a role in that world, not just as an OS, but as the layer that abstracts workload orchestration, model management, security, and privacy.

And because Microsoft also owns the cloud (Azure), it’s uniquely positioned to bridge edge and cloud, coordinating AI workloads across both.

We’ll unpack below.

But first, local inference must enable experiences you can’t get from the cloud alone. The skeptic might ask, “Why not just run everything in the cloud?” That’s where most GenAI workloads live today after all…

Anticipatory AI

Local AI can unlock user experiences that wouldn’t otherwise be possible, primarily for economic reasons.

I call these “anticipatory” experiences.

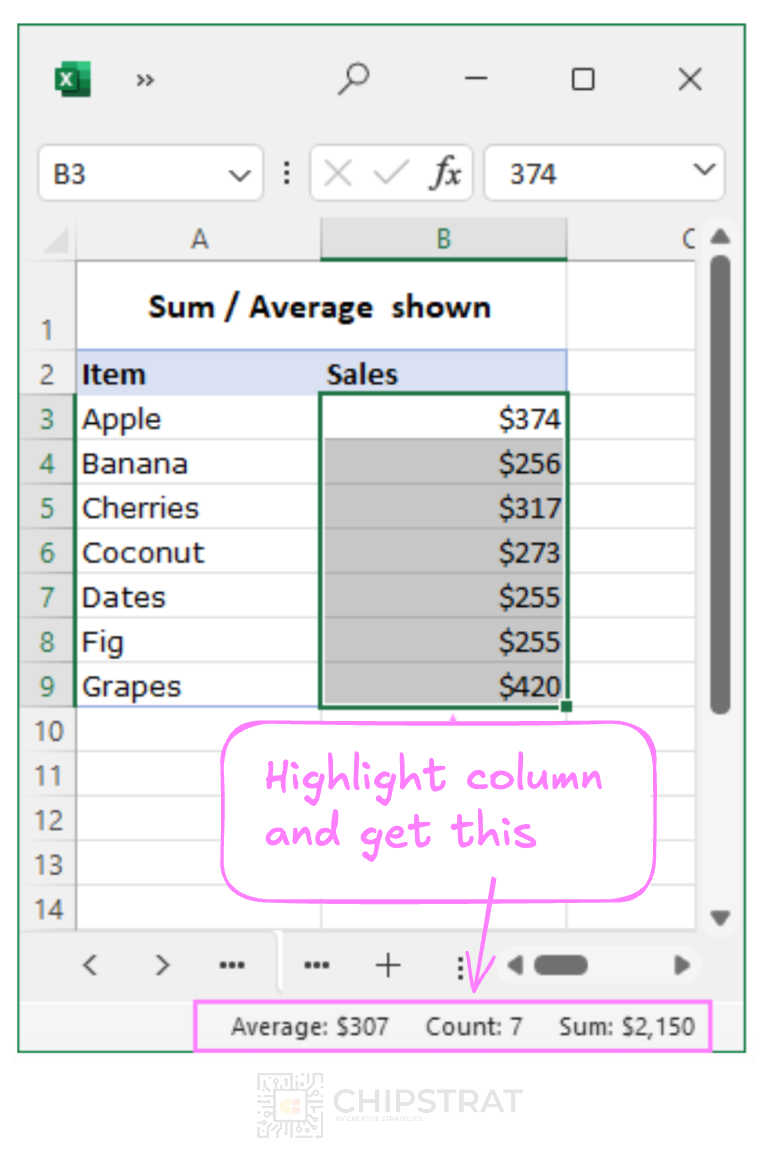

An example of an existing simple anticipatory experience is when Excel runs some quick math on a highlighted column of data:

But this is basic anticipation. It doesn’t examine your actions or the rest of the spreadsheet to offer anything relevant to your context.

Generative AI changes that. With local models, we can build smarter, more useful anticipatory features.

After all, Excel already tracks your actions (that’s how undo works). What if your spreadsheet, action history, and related global context were passed into a local GenAI model? Excel could start to understand what you’re trying to do and proactively suggest tips that you actually need.

For example, imagine if Excel popped up a message to say:

Hey, I noticed you’re copying campaign names manually from one sheet to another based on email or phone number. Have you heard of VLOOKUP? It can save you hours by automatically pulling in matching data from a separate sheet!

And if you click to learn more, what if it said:

Here’s what it looks like you’re trying to do:

• Match customers from your Salesforce export to your Google Ads export

• Figure out which ad campaign led to each offline sale

• Manually search by email or GCLID

• Copy-paste campaign names one row at a timeThat’s a perfect case for VLOOKUP! Use it to join any two tables like GCLID to lead. Want help setting it up? Just say the word!

Wouldn’t that be amazing?! That’s more than just autocompleting the next formula you might be typing; rather, it understands that you’re a marketing analyst trying to figure out which marketing campaign or ad click led to a phone conversion or final sale. And this assistant could interactively guide you through the process.

And here’s where local AI comes in. This kind of anticipatory work runs silently in the background, always on.

Every time you do something, Excel could quietly try to figure out what you’re doing and whether it can help. Only when it’s highly confident you need a hand would it offer a subtle nudge. That means say 95% of the time, it’s just watching and thinking. That might seem wasteful. But the 5% when it’s helpful? It could be really helpful. Helpful enough to justify all the continuous background computation.

In that way, it’s like venture capital. Many misses. A few home runs. And the wins more than pay for the cost of all the at-bats.

This continuous, anticipatory inference isn’t cost-effective at scale with cloud inference.

Microsoft isn’t going to ship every Excel keystroke to the cloud. With millions of users, that would mean billions or trillions of daily inferences for this one workload. It would crush the network and eat up cloud accelerator time.

But with local AI, it’s doable! Especially on devices with NPUs. When you launch the Excel app, a small reasoning model fine-tuned for this task could load into memory and run quietly in the background. No network strain. No cloud costs. No privacy risk.

What does it cost the user? A bit of battery. But NPUs were built for this, and can provide continuous low-power inference. Even if it runs on every keystroke, it could sip just a few milliwatts at a time.

This doesn’t require a giant model, just a small one that can reason and has been fine-tuned on everyday Excel habits and mistakes. It also doesn’t need blazing speed. Sure, it could run on the GPU, and on older laptops, it probably would. But speed isn’t the goal. Low power is. That’s where the NPU comes in.

The Return of the OS

This is where the operating system matters again. There’s real work to manage on the user’s behalf: keeping the base model updated, loading an app’s fine-tuned adapter when it opens, routing the workload to the NPU, but falling back to the GPU when needed. The OS must also support a toolchain so developers can build and bundle their adapters. And it has to do all this securely.

Microsoft is doing this.

Moreover, Microsoft is uniquely positioned to enable hybrid inference, letting developers split workloads between the cloud (Azure) and the device (Windows PC). Can Azure’s enterprise AI competitors like AWS do that?

Windows Announcements

Windows can matter again, and Microsoft is leaning in.

Microsoft just introduced Windows ML, a new runtime for fast, on-device model inference. It simplifies deployment by letting developers ship AI apps using ONNX models, without tailoring them to each hardware setup.

Remember the orchestration bit we talked about? Here’s what Windows ML says:

It’s built to help developers leverage the client silicon best suited for their specific workload on any given device – whether it’s an NPU for low-power and sustained inference, a GPU for raw horsepower or CPU for the broadest footprint and flexibility.

Leverage device policies to optimize for low-power, high performance, or override to specify exactly what silicon to leverage for a specific model. In the future this will enable split processing for optimal performance – leveraging CPU or GPU for some pieces of a model and NPU for others.

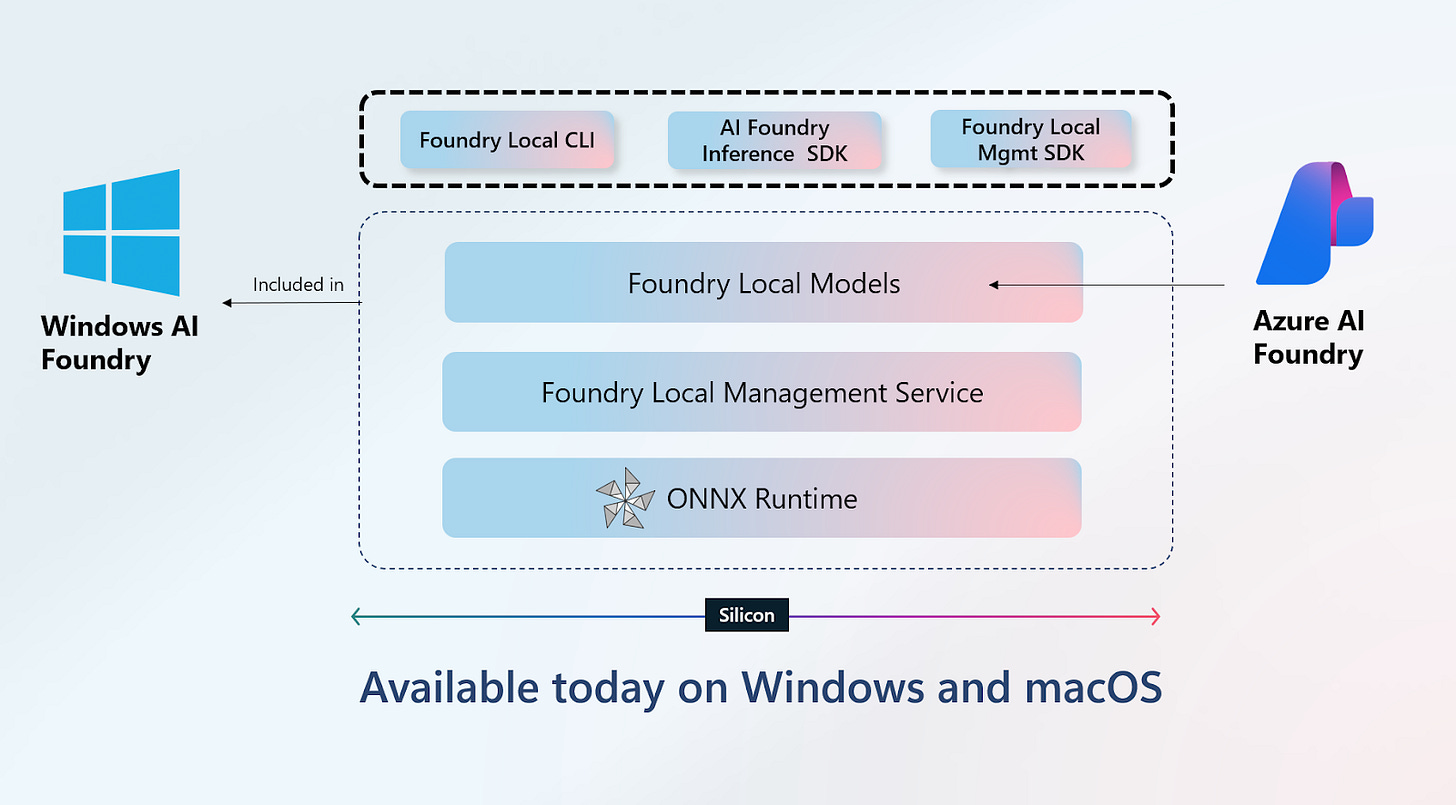

Microsoft also announced Windows Foundry Local, a cross-platform (Windows + macOS) local AI runtime stack for running not just models but agentic apps and tools. It is designed to bridge cloud and edge, and even supports Model Context Protocol (MCP) for calling local tools.

Meet Foundry Local—the high-performance local AI runtime stack that brings Azure AI Foundry’s power to client devices. Now in preview on Windows and macOS, Foundry Local lets you build and ship cross-platform AI apps that run models, tools, and agents directly on-device. It is included in Windows AI Foundry, delivering best in class AI capabilities and excellent cross-silicon performance on hundreds of millions of Windows devices.

For the first time in decades, the OS might again be a primary integration point for developers.

Windows is no longer just where thin clients run. It’s becoming the layer that manages AI inference, abstracts over diverse hardware, and connects edge and cloud.

Microsoft is rebuilding its relevance from the ground up: loading local models, routing workloads, managing privacy, and giving developers new building blocks.

But none of it matters if developers don’t use it.

So the real question is not just can Windows matter again, but what must Microsoft do to make it happen? Let’s dig in behind the paywall.