Lithography Economics

The Problem With Lithography. ASML, xLight, Substrate.

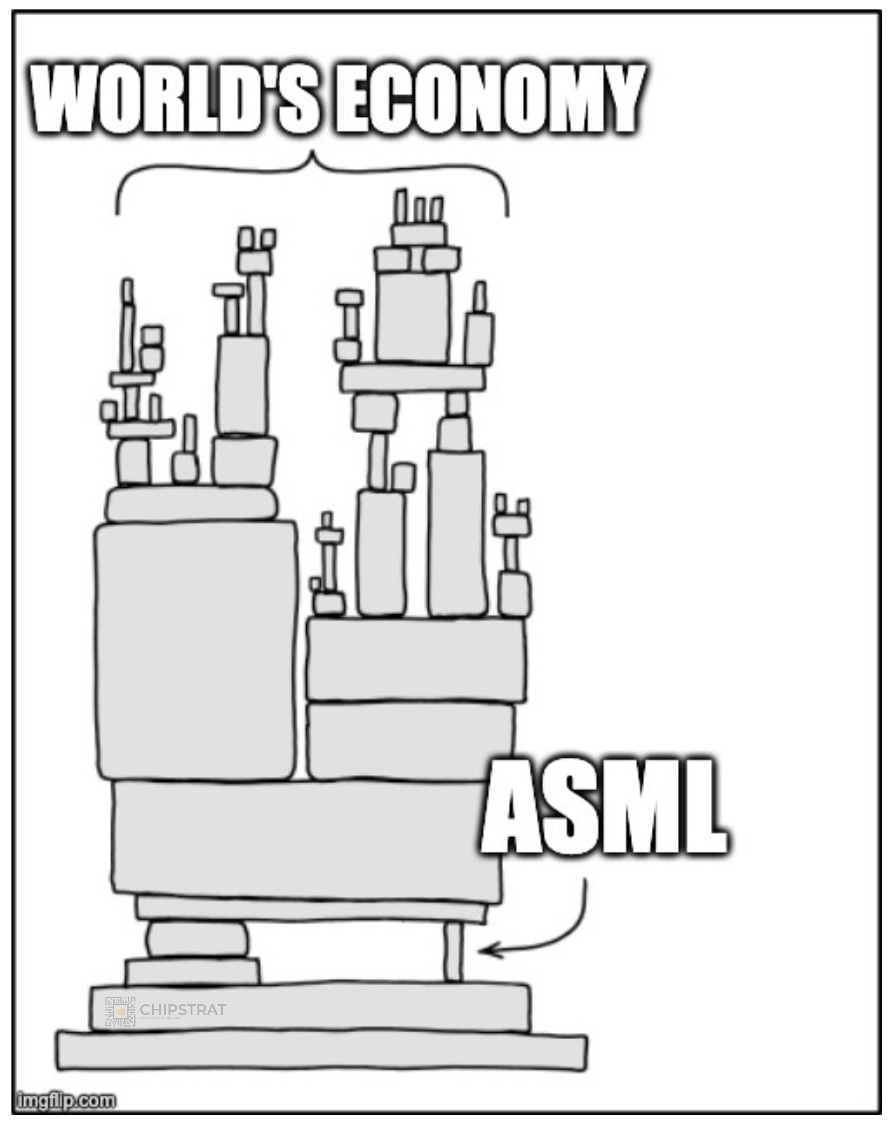

ASML is the world’s sole supplier of EUV lithography systems, the machines required to manufacture leading-edge semiconductors. The Mag 7 depends very heavily on leading-edge semis. Nvidia. Apple. Google. Even Tesla, whose market cap depends heavily on the promise of autonomy, needs leading-edge semis for model training.

Speaking of AI, the entire AI revolution depends on leading-edge semis! Productivity gains across nearly every industry ultimately trace back to EUV capacity, and therefore to ASML. After sitting on it for a bit, I inevitably end up here:

And thanks to Marc Hijink’s great ASML book (Focus), I know that EUV competition isn’t so simple; ASML is the orchestrator of a very complex supply chain. It’s a bit fragile too (lone dependency on Zeiss optics) which makes it even harder for new entrants. You think ASML will let Zeiss sell you mirrors for your competitive attempt?

That leaves only nation-states that can stand up entire supply chains as willing competitors, namely China. There are obviously geopolitical implications here.

So any talk of EUV over the past few years is generally “invest in ASML” and “watch out for China in 2030”. But there’s a lot less talk about the underlying problem with lithography, namely, one of economics.

Let’s take a step back. What happens when a market is a virtual monopoly? The price of the goods or services can start to run up and to the right. This is no knock on ASML, nor TSMC for that matter. Both are very well-earned near monopolies.

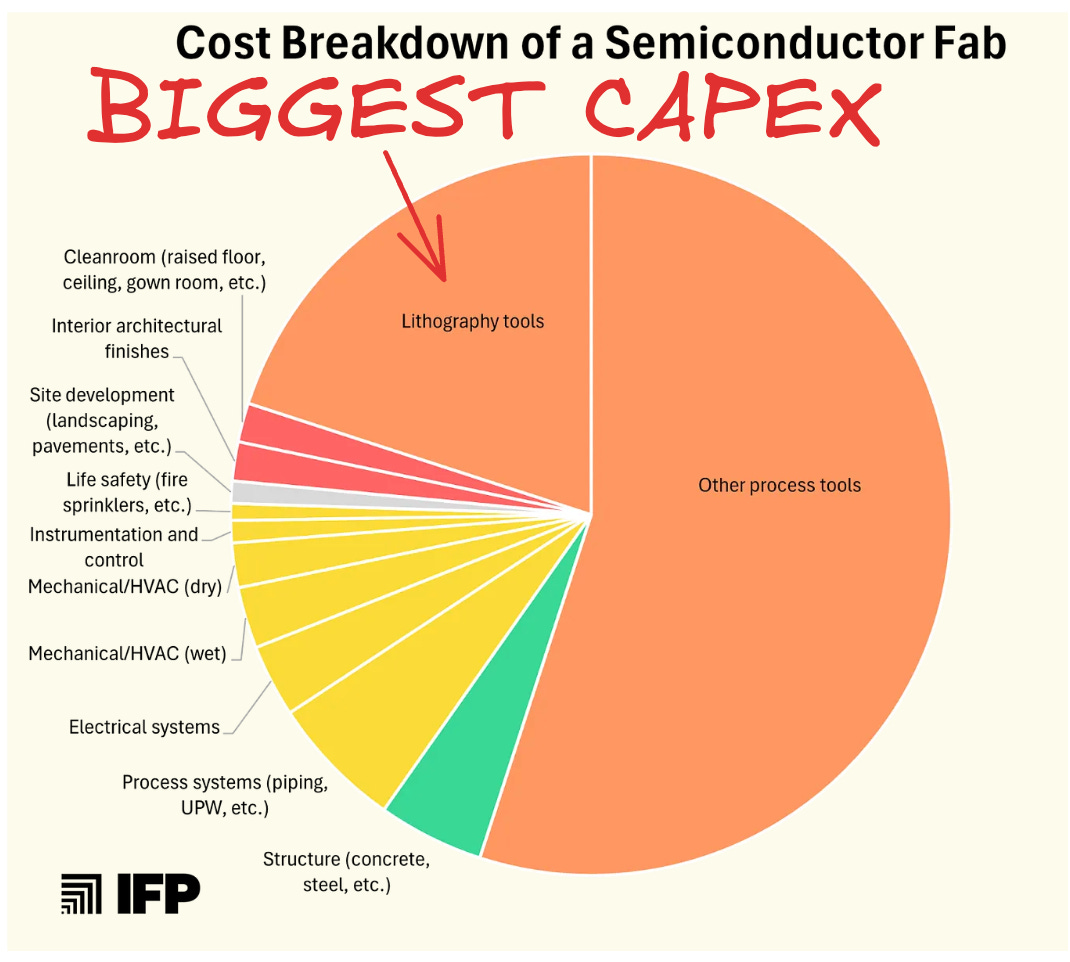

But the cost of future EUV machines is on a path toward $1B per machine in the 2030s. And that’s a big driver of the cost of wafers on a path toward $100K per wafer in the 2030s.

ASML’s near-monopoly isn’t the problem. ASML is a great company doing great things, and they’ve earned their keep. The problem is economics. Current EUV tools cost around $250M a piece, next-gen tools are on the order of $400M or so, and rumored future versions could run $600M+.

But with no competition, nothing’s going to stop that inevitability, right?

Nah, come on. If there are dollars on the table, someone will try to compete.

In fact, in the latter half of 2025, two US-based companies announced they are tackling the problem of lithography economics.

The first is xLight, a Palo Alto team “building the world’s most powerful Free Electron Lasers”.

The second is Substrate, a San Francisco-based company “harnessing particle accelerators to produce the world’s brightest beams, enabling a new method of advanced X-ray lithography”.

Both xLight and Substrate address the same constraint: the punishing economics of leading-edge lithography. But they are taking fundamentally different technical approaches to reduce lithography costs. This pushes each down separate paths with different:

Customers, route-to-market, and TAM

Funding requirements

Risks and timelines

But before we can understand the rationale behind each startup’s approach, we must first understand the problem itself. Why is lithography so expensive? That’s what this post sets out to address.

Now, first, a quick personal aside on why I’m cheering for xLight and Substrate.

Physics. Science. Heck Yes.

I grew up in rural Iowa. Population around a thousand. I played sports, went to church, did fine arts, and spent time with friends and family. I was not optimizing for elite colleges, careers, startups, or Wall Street. Our school offered exactly zero AP courses. I graduated and went to the local state school to study engineering, which was considered quite ambitious for our area. But I took two things with me: a Midwestern work ethic and the belief that a great way to honor God is to make the most of each day’s opportunities. Get up and grind, for His glory.

And Iowa State had those opportunities for the taking. I learned to code and built a robot. I took Physics, Math, Electrical Engineering, and Computer Architecture courses. I worked as an undergraduate research assistant, building an electrostatic levitation (ESL) system from scratch for studying condensed matter physics.

We did condensed matter physics experiments. We would place a sample in a vacuum, levitate it electrostatically to eliminate container effects, and use a laser to heat and cool it while suspended. This allowed us to repeatedly cycle the material between solid and liquid phases and study undercooling, where a liquid remains below its equilibrium melting temperature during solidification. Simply put, a material can melt at one temperature when heated, but remain liquid and only solidify at a lower temperature as it cools.

Better yet, we brought an electrostatic levitation system to the particle accelerator at Argonne National Laboratory outside Chicago, where we probed the levitated samples with high-energy X-rays during cooling. This allowed us to observe atomic-scale structural changes during supercooling using X-ray diffraction.

My small claim to fame was modifying the ESL controller code to accept input, allowing precise left-right and vertical positioning of the floating sample to keep it aligned with the X-ray beam.

Dude.

I had zero experience and zero credentials, yet I was given the opportunity to get my hands dirty and contribute to real science.

I wondered if this is what it was like for some of the legends I read about in my free time like Robert Millikan or Robert Noyce.

From there, I launched into researching nanoelectronics at UIUC. I was making graphene-based transistors, so I’d gown up into a bunny suit and head into the cleanroom to run build some itty-bitty experiments.

While I was waiting for the fab tools to do their thing (deposition, etch, etc) I’d standby and read Paul Graham’s latest essay on the computer in the cleanroom. I was just as much interested in entrepreneurship and business and science and technology.

I even played a small role as a cofounder of a startup during that time, and had a blast and learned a ton launching on Kickstarter. We just came up with an idea, built a thing, and folks sent us money for it. You CAN just do things. The Internet is such a big place.

Not too long later I left academia for industry and startupland because I was just itching to build. Don’t get me wrong, grad school was peak intellectual stimulation and I loved that. But publishing papers that maybe 100 people would read also felt a bit, I don’t know, underwhelming. Granted some of our work might be adopted in a decade. But I was itching to build something with a nearer-term, bigger impact. So off I went.

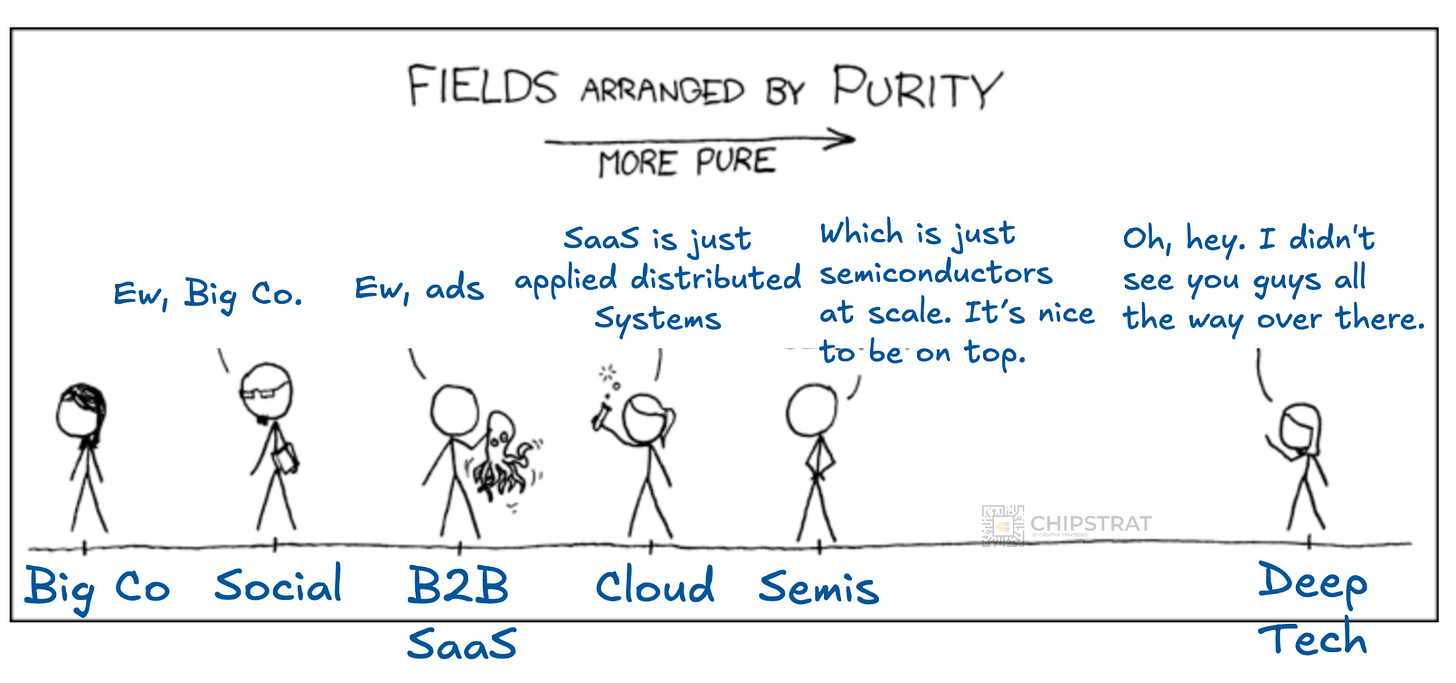

Unfortunately, the 2010s were a pretty lame time to build.

Want to be an entrepreneur? Sure. Here’s some money, so long as it’s social media or B2B SaaS.

Bleh. Dude. That’s as far from science and physics and real technology as possible. Maybe the world just doesn’t incentivize making real technology anymore? Was it even possible to be both an entrepreneur and work on the far right side of the spectrum? Deep tech. Physics. Science. Math?

Well, my timing was off. But all good. The time is now. And that’s exactly why I’m cheering for xLight and Substrate. Both involve particle accelerators! And entrepreneurship! And they are actually getting material funding!

What a time to be alive.

To be fair, some have been pushing on Deep Tech for some time now. For example, in 2017, this Founders Fund manifesto asked “What happened to the future?” and proclaimed “We invest in smart people solving difficult problems, often difficult scientific or engineering problems.” No surprise that Founders Found is an investor in Substrate.

Packy McCormick has been writing about it lately too, highlighting heavy CapEx startups that VCs were previously afraid of, from Deep Tech like Solugen to Techno-Industrials like Anduril to Vertical Integrators like SpaceX.

And for business strategy lovers, this is going to be a fun case study to watch in real-time. Not only are xLight and Substrate capital-intensive and working on cool science, they are encroaching in an arena which everyone says is impossible to enter. Goliath (ASML) is untouchable.

Come on! It doesn’t get better than this! The problem matters. The solutions are genuinely interesting. And there is real skepticism to overcome.

And yes, this may ruffle some feathers, but I would rather live in a world where our kids accelerate particles, build robots, and discover new science, than one optimized for folks to spend their hard earned education building infinite scrolling apps full of low-effort AI content.

That is the world I want. Which is another reason why I am rooting for startups like xLight and Substrate!

Lithography Economics Are The Problem

Now, back to the problem of lithography economics.

We can’t truly analyze the pros and cons of xLight and Substrate’s approaches without first understanding the worsening economics of lithography.

Come along with me. We’ll hit important basics, including

How multipatterning impacts tool count and throughput requirements

Why EUV doesn’t eliminate multipatterning

Why High-NA improves resolution but does not solve the cost curve

Why fabs will need both Low-NA and High-NA EUV at scale

Hyper-NA, and why it’s even more expensive